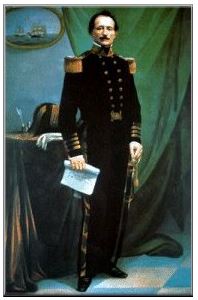

There have been many Jews in the United States Armed Forces and many Jewish heroes in all of America’s wars. Many members of Mikveh Israel served with distinction throughout the history of the United States, with many of them making the ultimate sacrifice in service to their country. Perhaps the most famous of all of them, though, was Uriah Phillips Levy, the first Jewish Commodore in the United States Navy.

Uriah Phillips Levy was born on April 22, 1792 (30 Nissan 5552), and though the country itself had just won its independence 8 years before his birth, his American roots ran deep. Uriah was the grandson of Jonas Philips, who was instrumental in the construction of the first synagogue building of Mikveh Israel, solidifying the congregation and serving as Parnas at the time of its dedication.

Jonas Phillips was born in 1735 in Prussia, though of Spanish descent, and arrived in Philadelphia via Charleston, New York, and London, in 1762 where he married Rebecca Mendes Machado, the daughter of a former Hazan of Shearith Israel Rev. David Mendes Machado. Rebecca was only 16 years old at the time. It is told that George Washington attended and danced at their wedding in Plymouth Meeting, PA, being listed among the guests as “a planter from Virginia”.

Jonas failed in his first few attempts at business, first in retail and then as an auctioneer, and had to resort to performing duties as a Shohet (ritual slaughterer) for Congregation Shearith Israel in order to feed his growing family. Eventually, he would have 21 children, almost all of them surviving to adulthood and most of them becoming prominent members and leaders of Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, Shearith Israel in New York and the secular communities in both cities. After New York proved to be a difficult place for Jonas to become successful, he finally moved the family permanently to Philadelphia in 1774, where opportunity was abundant and success came to him more easily. He went into the dry goods business and eventually became the second richest Jew in Philadelphia, according to city records.

Jonas Phillips was an ardent patriot and strong believer in the American cause. He was also a proud Jew who publically advocated for the rights of his brethren and led his congregation by example. This was a strong influence on his grandson Uriah with whom he was very close, and which guided and strengthened the young man during his entire lifetime, where he faced adversity through anti-Semitism and jealous rivalry.

In 1787 Jonas Phillips’ daughter Rachel, whose twin sister had died in infancy, married Michael Levy. Their wedding was an elaborate one which is described in detail in a letter written by Dr. Benjamin Rush to his wife. This is the only known surviving written description of a Jewish wedding from the 18th century. Not much is known of Michael Levy. Many stories were told by his grandson and Uriah’s nephew, Jefferson Monroe Levy, about how Michael descended from Asser Levy, who was one of the original 23 Jews to land in New Amsterdam (later New York) in 1654, but these stories have long since been disproved. We know that Michael Levy was a charter member of the German Ashkenazic congregation Rodeph Shalom in 1802, and therefore was very unlikely to have descended from the prominent families of the Spanish and Portuguese congregations. He was born of a German family in London in 1755, and likely came to America, possibly Virginia, when he was about 10 years old. He did serve in the American army during the Revolution. His profession was making and selling clocks and watches.

In 1770, Jonas Phillips had been a signer and strong supporter of the New York Non-Importation Agreement. In 1776, when the British occupied Manhattan, Phillips used his influence to close down Shearith Israel rather than continue under the British. Phillips himself had already removed his wife and 15 children to Philadelphia and many of the members of the New York Congregation followed him there. In 1778, Phillips joined the militia in Philadelphia, enlisting as a private under Colonel Bradford. After his service, he supplied the continental army with dry goods, food items, and other needed materials. Following the war, he appealed to President Washington and the Continental Convention drafting the new Constitution of the United States in a letter dated September 7, 1787. His concern was that all office-holders in the new government were to be required to swear allegiance over the Christian Bible. He writes, “to swear and believe that the New Testament was given by divine inspiration is absolutely against the religious principle of a Jew and is against his conscience to take any such oath”. In his eloquent and impassioned letter, he argues that, “during the late contest with England [the Jews] have been foremost in aiding and assisting the States with their lives and fortunes, they have supported the Cause, have bravely fought and bled for liberty which they cannot enjoy”. He wrote the letter for “my children and posterity and for the benefit of all the Israelites throughout the 13 United States of America”.

Against this backdrop, and with a strong guiding influence from his grandfather, Jonas Phillips, Uriah Phillips Levy began his long and successful service to his country and his people. He was drawn to the sea from a very early age, spending a lot of time on the docks of Philadelphia watching the great sailing ships and learning their names and flags as they came in and out of port, loading and unloading their cargo. In 1802, at the age of 10, Uriah ran away from home in the middle of the night to join the trading ship New Jerusalem as a cabin boy. He accepted a 2-year appointment and returned to his family and synagogue just in time for his Bar Mitzvah at Mikveh Israel. After trying and failing to convince the young Uriah to join the family business in retail trade, Uriah’s father in 1806 apprenticed him for four years to one of Philadelphia’s leading ship-owners and a close family friend, John Coultron. Uriah served as a seaman on the schooner Rittenhouse. In 1807, President Jefferson imposed an embargo on all trade with Europe, idling the ships and leaving nothing for Uriah to do. Mr. Coultron took this opportunity to send his young apprentice to a school for navigation led by an ex-lieutenant of the British Navy. When the embargo was lifted, Uriah was off again to sea with far more skills and maturity than before.

By the time he was 18, Uriah had already made several profitable voyages, serving in all of the different capacities during his apprenticeship including cabin boy, ordinary and able-bodied seaman, boatswain, third, second, and first mates, and captain. By the age of 19, Uriah had earned enough money to purchase a one-third interest in a trading ship, the new schooner called the George Washington, named for the first names of his two partners George Mesoncourt and Washington Garrison. When not at sea, Levy was very careful to carry his certification of American citizenship, as British impressment gangs prowled the city looking for young men to force into service in the British Navy. These “protection papers” were usually enough to thwart impressment, so Uriah wasn’t worried when a squad of British marines from the Vermyra approached him. On showing them his credentials, they remarked “You don’t look like an American. You look like a Jew.” Uriah Levy replied, “I am an American and a Jew.” After an insulting remark, the hot-headed Levy displayed the high-handed defensive spirit and refusal to be denigrated that shaped his stormy career throughout his life. He was pressed into service against his will and forced to serve on the Vermyra for a month before he was released. During that time, the commander of the ship, recognizing Uriah’s skills and spirit, repeatedly demanded that Levy join the British Navy. Levy refused, stating “Sir, I cannot take the oath. I am an American and cannot swear allegiance to your king. And I am a Hebrew and do not swear on your testament, or with my head uncovered.” Finally, after an audience with the British Naval Commander in Jamaica, his papers were deemed to be in order and he was released on the condition that he find his own way home.

On one of his first trips commanding the George Washington, Levy picked up a cargo of corn which he sailed to the Canary Islands and sold for 2,500 Spanish dollars and fourteen cases of Teneriffe Canary wine. On his way back to the States, his crew mutinied, stealing the ship, the money and the cargo. Levy barely escaped with his life. Using another ship and determined to bring the mutineers to justice, he hunted them down, finally finding and overtaking them in the Caribbean. He brought them back to Boston, where the leader was hanged and an accomplice received a life sentence.

By the time he arrived home in 1812, the United States had declared war, for the second time, against Great Britain. Levy, barely 20 years old, chose to serve his country in the war over a lucrative career as a privateer. He chose to apply for a commission as a sailing master over the more usual entry as a midshipman. The sailing master handled all aspects of navigation and during sea battles took over the operation of the ship while the captain directed the fighting. Later he explained his choice, saying “I sought this particular position in the belief that my nautical education and experience would enable me to render greater service to my country”. His commission from President James Madison came through in October, 1812, and he was assigned to the USS Argus, where his first assignment was to transport William H. Crawford, the new minister to France, to his post in order to entreat the French for support during the war. After depositing Crawford safely in France, the Argus began a short but very successful run as “the dreaded ghost ship” that attacked and destroyed much larger British ships in the Channel. Levy received a temporary promotion to Lieutenant and assigned the task of boarding, destroying, or commandeering the captured ships. While transporting a valuable ship, the Betty, to a French port, the Argus was finally overpowered and destroyed, with the captain and most of the crew killed. Meanwhile, the unarmed Betty was captured, and Levy spent the duration of the war in prison until he was released in a prisoner exchange after the war.

Levy was assigned to the USS Franklin in 1816. He was met there with prejudice and ostracism. Soon afterwards, while dancing in full uniform at the Patriot’s Ball in Philadelphia, a somewhat drunk Lieutenant William Potter bumped Levy on the dance floor. After a second and then a third forceful collision, Levy turned and slapped Potter across the face. Enraged, Potter cursed Levy as a Jew, to which Levy responded, “That I am a Jew, I neither deny nor regret”. The two were separated and Potter led away. The following morning, Levy received a formal challenge to a duel. Levy was not anxious to fight a man over a dance-floor incident and offered to shake hands and forget the whole thing. Potter refused and they agreed to a pistol duel in a meadow in New Jersey, as dueling had been outlawed in Pennsylvania. Asked by the judge if he had anything to say, Levy asked permission to utter a prayer in Hebrew, the Shema, and then said, “I also wish to state that, although I am a crack shot, I shall not fire at my opponent. I suggest it would be wiser if this ridiculous affair be abandoned”, to which Potter replied, “Coward!”. Levy gave Potter the first shot, which went wide. Levy then simply pointed his pistol in the air and fired. Potter reloaded a second round and fired, again wide of the mark. Levy reloaded and again fired into the air. A third and fourth shot missed Levy, each time returned with harmless shots into the air. Finally, a fifth shot nicked Levy’s ear. After Potter loaded for a sixth shot, Uriah took careful aim and fired into Potters chest, killing him instantly. The affair created quite a stir in Philadelphia and the press who praised Levy for his honor. He was acquitted during his subsequent court martial. Judged to not have been the provocateur nor the aggressor, his case was dismissed. He was also acquitted by a jury in the civil indictment brought against him.

Following this incident, Levy received his official promotion to Lieutenant. The jealousy and prejudice expressed both by those passed over in favor of Levy and among those whose ranks he joined began a career of ceaseless persecution and undeserved punishment simply because he was a Jew. Back in Philadelphia, a friend took him aside and strongly advised Uriah not to pursue a career in the Navy. He warned him that though nine of ten commanding officers wouldn’t care that Levy is Jewish, the tenth will make his life hell. According to his memoirs, Levy responded, “What will be the future of our Navy if others such as I refuse to serve because of the prejudices of a few? There will be other Hebrews, in times to come, of whom America will have need. By serving myself, I will help give them a chance to serve”.

Three years later, his troubles resumed while serving as the third lieutenant aboard the United States. On presenting himself for duty, he was rejected twice by the captain on account of his being a Jew. The commodore had to get involved to secure the position. It was aboard the United States that Uriah witnessed his first flogging. He was so horrified that he worked for the rest of his career to end the practice. After getting into a fight with another lieutenant over a small issue, the vindictive captain ordered a court martial and had Levy dismissed from the Navy. President Monroe reviewed the case and reversed the decision. But by the time this had happened, Levy had another fight over an even more trivial matter and now faced court martial number three. In his defense, he accused his fellow officers of anti-Semitism. He made a long and impassioned speech complaining of being unfairly treated because of his faith. The court was unsympathetic and returned a verdict of guilty and dismissed him from the Navy in disgrace. After spending a couple of years wandering around Europe and living for a time in Paris, he finally returned home to some astonishing news. After two years, his case finally reached President Monroe’s desk for review. Monroe decided that Levy’s offense was not sufficient for dismissal and the suspension he already served was punishment enough, and he was restored to his position. A fourth court martial over another verbal volley of insults resulted in a draw, both the accuser and the accused being reprimanded.

In 1825, Uriah was serving as second lieutenant on the Cyane, which was stationed off the coast of Brazil. While the ship was in port for repairs, Levy witnessed an American seaman being seized by a Brazilian press-gang. The young man called for help. When Levy’s midshipman stepped in to rescue the boy, he was attacked by the Brazilian officer who slashed at him with his saber. Levy stepped in and received the blow, saving the midshipman’s life while incurring slashes to his wrist and his rib. The following day, he received a visit from the Emperor of Brazil Dom Pedro. Pedro had been so impressed with Levy’s bravery that he ordered that Americans were not to be ever again pressed into service of the Brazilian Navy. He then offered Levy a commission in the Brazilian Imperial Navy on its newest ship that had just been built in the United States. Levy politely refused, telling the Emperor, “I would rather serve as a cabin boy in the United States Navy than hold the rank of Admiral in any other service in the world”. Levy became very popular, however his views on flogging were not. He used humiliation as an alternative punishment, which was not appreciated by his fellow officers.

Once again, he exchanged words with another officer after his honor, integrity and religion were insulted. He responded by challenging the officer to a duel. A fifth court martial resulted, ending in a public reprimand for Levy. He counter-sued and won, leaving the other officer suspended for a year. This did not endear him to his fellow officers who ostracized and ignored him. Bitter and dejected, Levy asked for and received a six month leave of absence. His commanding officer wryly offered to extend the leave indefinitely, to which Levy inquired if this was because he was a Jew. The officer replied that it was. Levy moved to New York City, where he decided to invest his Navy savings in real estate. Within four years he had become very wealthy. In 1833, he commissioned Pierre Jean David d’Angers to sculpt a statue of Thomas Jefferson, whom Levy considered “one of the greatest men in history”. Levy had the statue delivered to the Capitol with a letter, and after some discussion, Congress finally accepted the gift and placed it in the Rotunda where it stands today.

Jefferson had died on July 4, 1826 on the 50th anniversary of the United States. His house, Monticello, and its grounds went to his daughter Martha. After two years, she couldn’t afford the upkeep and offered it for sale. No takers were forthcoming at her asking price of $71,000, and she finally ended up selling it for a mere $7,000 to a man who intended to use the land for growing silkworms. After that venture proved unsuccessful, he left the property abandoned, looted and neglected. Levy made a pilgrimage to the property in 1834 and finding it so run-down, purchased it for $2,700, resolving to restore it to its former glory. As he did so, he moved his mother Rachel Levy to live there permanently, and himself spent summers restoring the house and property. Rachel is buried on the path to the house. In his will, Levy left the house to the People of the United States, or failing that, to the State of Virginia. As it turned out, neither was interested in taking it, so after some time Uriah’s nephew, Congressman Jefferson Monroe Levy, bought out the other heirs and once again restored the property, searching throughout the United States for authentic Jefferson furniture to fill the house. In 1923, Jefferson Levy sold the house and property to the Monticello foundation.

Meanwhile, Levy had been petitioning the Navy throughout his leave requesting duty. Finally in 1837, he was promoted to Commander after 20 years as lieutenant. The following year he received orders to take command of the Vandalia. He took this opportunity to eliminate the practice of flogging in favor of new rules for conduct and discipline. As a result of an incident involving a humiliating punishment given to one of his men, he was again court martialed for a sixth time. Once again, he was dismissed from the Navy amid much discrimination on the part of the court. This time, it was President Tyler who reversed the decision, deciding that the ruling against Levy had not been made for the good of the service. He agreed with Levy that flogging should only be used as a last resort and avoided whenever possible. Upon the recommendation of the President, Levy was promoted to Captain. While petitioning for an active duty assignment, Levy devoted time to lobbying the flogging issue and writing pamphlets in support of his cause. Despite opposition from the Navy, an anti-flogging rider was attached to the Naval appropriations bill of 1850 and the practice of flogging was finally outlawed in 1862.

In 1855, after petitioning for years for an assignment, Levy, along with 200 other officers, were dismissed from the Navy. Levy was enraged, suspecting discrimination once again and hired a lawyer, Benjamin Butler, who wrote a letter to petition congress to restore Levy to his post. Congress convened a Court of Inquiry in 1857, and the following year Levy along with about a third of the other officers were restored to active duty. Four months later, Levy was given orders to take command of the Macedonian in the Mediterranean squadron, and given the rank of Commodore.

Uriah P. Levy died on March 22, 1862 (Adar II 20, 5622). The navy honored him by launching the USS Levy during World War II. At a ceremony on Friday December 16, 2011 attended by hundreds, a 6-foot high bronze statue of Uriah P. Levy was dedicated at Mikveh Israel. The statue, designed and sculpted by Gregory Pototsky, sits on the Fifth St. lawn facing Independence Mall. The statue and its dedication were made possible by Navy Captain Gary “Yuri” Tabach and Joshua Landes, in association with the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs. Landes served as the master of ceremonies for the dedication. Addresses were given by Landes’ father, Retired Rear Admiral and Rabbi Emeritus of Congregation Beth Sholom, Aaron Landes, John Lehman, former Secretary of the Navy, Rear Admiral Herman A. Shelanski, and a number of other distinguished speakers. A video of the dedication ceremony can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZLWBo-IrRiA.

Uriah Phillips Levy was a proud, determined, forthright, and some would even argue pugnacious man. He was fiercely patriotic and loyal to his country, while at the same time proud of his people, his religion, and his heritage. He was ready at all times to sacrifice his life and his honor in defense of his country or his religion. These qualities were instilled in him from a very early age by his family and he spent his entire life fighting injustice, intolerance, and discrimination. As Levy himself put it, “I am an American, a sailor, and a Jew”.

(click image to enlarge)

(click image to enlarge)

Bibliography:

- Americanjewisharchives.org

- Jacob Rader Marcus, Early American Jewry, 1955

- Wolf, Edwin, II, and Maxwell Whiteman. The History of the Jews of Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the Age of Jackson. (1957)

- Melvin I. Urofsky, The Levy Family and Monticello, 1834-1923: Saving Thomas Jefferson’s House, 2001

- Marc Leepson, Saving Monticello, 2001

- Stephen Birmingham, The Grandees: America’s Sephardic Elite, 1997

- Simon Wolf, Biographical Sketch of Commodore Uriah P. Levy, American Jewish Committee, Jewish Publication Society, 1903

- Rachel Pollack, Biographical Note to the Uriah P. Levy Collection, American Jewish Historical Society, 2004

- Henry Samuel Morais, The Jews of Philadelphia, 1894

- James Morris Morgan, An American Forerunner of Dreyfus, The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, 1899.

- Jewishsphere.com, Jewish War Heroes from 1775, 2009

- Fifty years’ work of the Hebrew Education Society of Philadelphia: 1848-1898

- Ellen M. Umansky & Dianne Ashton, Four Centuries of Jewish Women’s Spirituality: A Sourcebook, 2009

- Erika Piola, Jewish Women’s Archive, Jewish Women, A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia

Howdy! I could have sworn I’ve been to your blog before but after

going through a few of the articles I realized it’s new to me.

Anyways, I’m definitely happy I stumbled upon it and I’ll be book-marking it and checking back regularly!

It’s an awesome article in favor of all the web visitors; they

will take benefit from it I am sure.

Greetings from Florida! I’m bored to tears at work so I decided

to check out your blog on my iphone during lunch break. I

really like the information you provide here and can’t wait to take a look when I get home.

I’m shocked at how quick your blog loaded on my mobile ..

I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G .. Anyways,

awesome site!

this is great! thank you! where is the letter describing the wedding of Uriah’s parents?

Thanks Ronnie —

A nice version of Benjamin Rush’s letter to his wife can be found here:

http://books.google.com/books?id=sOwcwe-OW-wC&pg=PA37&lpg=PA37&dq=benjamin+rush+wedding+of+michael+levy+and+rachel+phillips&source=bl&ots=vXxhH6xbEi&sig=ef0wfS_NdXT7f_WGi1M2USTLaGI&hl=en&sa=X&ei=kGRxUZymJPXH4AOmn4Eo&ved=0CEgQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=benjamin%20rush%20wedding%20of%20michael%20levy%20and%20rachel%20phillips&f=false

I’ll put that link in the article.

Mark

Leon,

We do reference it on our website.

Lea

Lea Alvo-Sadiky

Executive Director

Congregation Mikveh Israel

44 North 4th Street

Philadelphia, PA 19106

http://www.mikvehisrael.org

lea@mikvehisrael.org

(215) 922-5446

(215) 922-1550 (fax)

(856) 979-1976 (cell)

From: Leon Levy [mailto:leon@leonlevy.com] Sent: Friday, April 12, 2013 11:54 AM To: Mikveh Israel History Cc: lb_berry@yahoo.com; Lea Alvo Sadiky; Albert Gabbai Subject: RE: [New post] Commodore Uriah Phillips Levy (1792-1862)

This is great. It should be part of KKMI’s distribution. I’m talking about the entire blog and part of our archives.

Leon

Leon L. Levy

Leon L. Levy & Associates

1818 Market Street – Suite 3232

Philadelphia, PA 19103

Phone: 215-875-8710

Fax: 215-875-8717

Toll Free: 1-888-LEON-LEVY

Website: http://www.leonlevy.com

e-mail: Leon@leonlevy.com

This is great. It should be part of KKMI’s distribution. I’m talking about the entire blog and part of our archives.

Leon

Leon L. Levy

Leon L. Levy & Associates

1818 Market Street – Suite 3232

Philadelphia, PA 19103

Phone: 215-875-8710

Fax: 215-875-8717

Toll Free: 1-888-LEON-LEVY

Website: http://www.leonlevy.com

e-mail: Leon@leonlevy.com

As a Mikveh Israel member and Army Officer, The Commodore has always been an inspiration to me. This is an outstanding article! I would like to hear more about other KKMI members who have served in both the U.S. and Israeli services.

beShalom uBerakoth,

Thad

Truly beautiful, thank you for your careful and engaging account. We need to find someone to make a movie of parts of his life!

I agree it would make an awesome and engaging movie!

I have been waiting for this one!!! Tnx

I relish reading it…Eli