Home » People

Category Archives: People

Rev. Gershom Mendes Seixas (1745-1816)

This week (6 Tammuz) we commemorate the Hashcabah of Rev. Gershom Mendes Seixas, the first minister of Mikveh Israel, who died July 2, 1816. Rev. Seixas was born on January 14, 1745 in New York City, to Isaac Mendes Seixas and Rachel Levy. Rachel Levy was the daughter of Moses Levy, who was one of the most prominent merchants in New York at the time. Her brother was Nathan Levy, whose request for a parcel of land for a burial ground in Philadelphia in 1740 is considered to be the origins of Congregation Mikveh Israel, as the starting of a community often begins with the establishment of a sacred burial place. He was thus the first American-born minister of Shearith Israel, and one of the few American-born ministers of Mikveh Israel to the present day.

It’s interesting to note that Gershom’s mother, Rachel Levy, was Ashkenazi, which made Gershom half Sephardi and Half Ashkenazi, mirroring the makeup of both the congregations in New York and Philadelphia. Seixas became the minister of Shearith Israel in July, 1768 at the age of 23. He had been born and raised in the Shearith Israel community. His teacher and mentor, Joseph Jessurun Pinto had served the New York congregation for 8 years before he suddenly had to leave for Europe in 1766. He later became the minister of the Sephardi community in Hamburg. After Isaac Cohen Da Silva served for a brief 2-year term, the Jewish community in New York, numbering only 300 people, unanimously elected the young Gershom Seixas as hazzan. Seixas served as the spiritual leader of the congregation, and also as the supervisor of Kashrut, performed all marriages and funerals, was the mohel, and for a time served as the shohet – the ritual slaughterer for the congregation.

At age 30, Seixas married Elkalah Cohen on September 6, 1775. Together they had 3 children over the next 10 years: Benjamin, who died unmarried; Sarah Abigail, who married Israel B. Kursheedt; and Rebecca Mendes, who also never married. Elkalah passed away in October, 1785. He then married Hannah Manuel on November 1, 1786, with whom he had 11 additional children. She was only 20 years old at the time of the marriage, and survived her husband by 40 years, living well into her 90th year. One of their children, David Mendes Seixas, was the founder of the Pennsylvania Institution for the Deaf and Dumb in Philadelphia, and was also a pioneer in discovering ways to burn anthracite coal.

Rev. Seixas was a strong advocate of American Independence, and has been given the nickname, The Patriot Jewish Minister of the American Revolution. In 1775, with the British Army fast approaching New York City, Seixas persuaded a majority of the congregation to close Shearith Israel rather than continue operating under the coming British occupation of Manhattan. He then packed up the Torah scrolls and other artifacts and books and moved them, along with his family, to his father-in-law’s home in Stratford, CT. In 1780, Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia invited Seixas to become the minister of the congregation. He arrived on June 6, and immediately began helping to create an established Jewish community in Philadelphia.

With the influx of members of Shearith Israel, including the leaders of the New York Jewish community, the number of Jews in the city grew from about one hundred, to over a thousand people. The New Yorkers, including Jonas Phillips, Hayman Levy, Gershom’s brother Benjamin Seixas, Simon Nathan, and Isaac Moses, used their experience at Shearith Israel to work with the Jewish leaders in Philadelphia, including Michael and Bernard Gratz, and Haym Salomon who had arrived some two years prior, to establish a form of prayer, a method of government, and a system of keeping records for the nascent Mikveh Israel. A Board of Adjuntos and officers were elected, and the congregation then began the project to design and build its first synagogue building. Seixas led the construction to its completion and carefully planned the consecration ceremony which was held in time for Rosh Hashanah in September, 1782.

At the close of the war in 1783, many of the refugees from New York returned to their homes and rebuilt the Jewish Community there. Congregation Shearith Israel invited Seixas back to New York to lead the congregation as minister once again. In spite of being established and comfortable in Philadelphia, he agreed, and , and four months after the British evacuated Manhattan, on March 23, 1784, Seixas resumed his duties as minister. He exchanged places with the minister in New York during the latter years of the war, Jacob Raphael Cohen, who came down to Philadelphia to serve as its minister. Each served their respective communities with distinction for the rest of their lives.

In addition to serving his own community, Seixas was very involved in the building of the greater Manhattan community as a whole. He frequently worked closely with the clergy of other faiths in fellowship for the greater good. Seixas was one of fourteen clergy to participate in the inauguration ceremony for George Washington as the first President of the United States. In 1787, he was invited to be a trustee of Columbia College, serving until 1815. He was one of the incorporators when Columbia was officially incorporated and his name appears in their charter. Upon his death, the Trustees, in gratitude, commissioned a memorial medallion with his likeness. He was also a trustee of the Humane Society, a member of the Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York. He also established a New York bet din for deciding disputes.

Seixas dedicated his life to serving the poor. He began many charitable organizations including the Hebra Hased Va’Amet – the first free burial society, and Kalfe Sedaka Mattan Besether – Fund for Charity and Anonymous Gifts. He frequently preached that the purpose of a fortunate person’s life was to help others, which they should do whether or not they receive a reward. He was profoundly grateful to his native land for providing a place for Jews to live and prosper without the worry of persecution. When preaching to the congregation, he gave “grateful thanks for the many and various blessings that have been graciously bestowed on us.” He established the Thanksgiving Day sermon, delivered first on the day of Thanksgiving and Prayer, proclaimed by President George Washington on November 26, 1789. He gave many more Thanksgiving Day sermons, in one he preached, “I conceive we as Jews are more called upon to return thanks to benign Goodness in placing us in such a country, where we are free to act, according to the dictates of conscience, and where no exception is taken from following the principles of our religion.”

His deep love of America did not dim his fervent desire for the restoration of Zion and the worship in the Temple. He would frequently pray for the people of Israel and would pray that God “restore us to our own land wherein we may dwell in Peace and in happiness according to the words of our sacred Prophets … Let us beseech Him to fulfill his divine promise of restoring us to our land, as declared in the prophesies, and that His sanctuary may again be built where we may perform our daily obligations.”

Rev. Seixas was not the only high-achieving, successful child of Isaac Mendes Seixas and Rachel Levy. His brother Benjamin was a prominent merchant in Newport, Philadelphia and New York, and was one of the founders of the New York Stock Exchange. He was also a member of the board of Mikveh Israel for many years. Benjamin’s son became the minister of Shearith Israel in 1828. Gershom’s brother Abraham served as an officer in the American army and carried dispatches for Gen. Harry Lee in the south. His brother Moses, the eldest, was one of the founders of the Newport Bank of Rhode Island. It was Moses Seixas who drafted a letter, in the name of the Newport congregation to George Washington upon Washington’s visit to Newport. Washington responded with a beautiful letter expressing his appreciation of the good wishes and his strong views in favor of religious tolerance.

The letter, so eloquently written, was delivered by hand to President Washington on his visit to Newport on August 17, 1790. Seixas, writing for his entire congregation writes, “Deprived as we heretofore have been of the invaluable rights of free Citizens, we now with a deep sense of gratitude to the Almighty disposer of all events behold a Government, erected by the Majesty of the People — a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance — but generously affording to all Liberty of conscience, and immunities of Citizenship: deeming every one, of whatever Nation, tongue, or language equal parts of the great governmental Machine.”

From the time the Revolutionary War ended and his return to Shearith Israel until his death in 1816, Rev. Gershom Mendes Seixas was the sole religious and spiritual leader of the New York Jewish Community. He was deeply loved by his congregation and well-known and loved throughout New York City. In his latter years, he was assisted by his friend and successor Moses Levi Maduro Peixotto, as well as by Emanuel Nunes Carvalho who was the head of the Shearith Israel religious school. In 1811, upon the death of Jacob Raphael Cohen, Carvalho moved to Philadelphia to become the minister at Mikveh Israel. In the first sermon known to have been delivered at Mikveh Israel, Carvalho said of Rev. Seixas, “His aspect was so benign, and his manners so courteous, that those with whom he conversed could not but feel themselves in the presence of a friend, and there was about him such an air of dignity, as always secured to him due respect.”

Bibliography

• Americanjewisharchives.org

• Edward Allen Fay, American Annals of the Deaf, Volume LVIII, 1913

• Wolf, Edwin, II, and Maxwell Whiteman. The History of the Jews of Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the Age of Jackson. 1957

• Henry Samuel Morais, The Jews of Philadelphia, 1894

• David and Tamar De Sola Pool, An Old Faith in the New World: Portrait of Shearith Israel 1654-1954, 1955

• N. Taylor Phillips, Rev. Gershom Mendes Seixas: The Patriot Jewish Minister of the American Revolution, 1905

• A Religious Discourse: Thanksgiving Day Sermon, November 26, 1789 by the Reverend Gershom Mendes Seixas, Jewish Historical Society of New York, 1977

Mikveh Israel and Christ Church

Wednesday, June 5, 2013 is the annual Fellowship Dinner between Christ Church and Mikveh Israel. Christ Church was founded in 1695. It was one of the first religious institutions in Philadelphia, and the first parish of the Church of England in Pennsylvania. Mikveh Israel is known as “The Synagogue of the Revolution” because of the active role played by many members of Mikveh Israel in the activities leading up to the Revolution, the Revolutionary effort itself, and the formation of the United States after the war was over. Similarly, Christ Church is known as “The Nation’s Church” because of the famous Revolution-era leaders who worshipped there. Among the parishioners of Christ Church were Benjamin Franklin, Betsy Ross, George Washington and John Adams.

The friendly relationship between Mikveh Israel and Christ Church goes back to pre-Revolution days. Benjamin Franklin organized 3 lotteries to raise money for the construction of Christ Church. Members of Mikveh Israel were among the people who purchased tickets and contributed money.

Later, in 1788, when Mikveh Israel was suffering financially after the Minister, Gershom Mendes Seixas, and several other members returned to New York after the revolution, the congregation sent out a solicitation to members of all faiths for support. The sum of 800 pounds needed to be raised, and after obtaining permission from the City, a lottery was established. Many of the members of Christ Church stepped up to help. One of the first contributors was Benjamin Franklin, who gave 5 pounds, a large sum for an individual donation at the time.

The close relationship between the two congregations was brought to public display on Independence Day, July 4th 1788. Philadelphia was the largest city in the country and where the Continental Convention had spent the last three years drafting the US Constitution. Though the Constitution was accepted by the Convention on September 17, 1787, it was finally binding on all the states when the ninth state, New Hampshire, ratified it on June 21, 1788, just two weeks before Independence Day.

Time for a parade! The morning of the 4th dawned to the peal of the steeple bell of Christ Church, followed by a cannonade from the ship Rising Sun, which was anchored off Market Street. Seventeen thousand onlookers gathered to watch successive troops of marchers. Each group were represented – professionals, artisans, farmers, and more. The military companies were first, then the ministers. The Pennsylvania Packet of July 9, in its account of the parade, reported, “the clergy of different Christian denominations, with the rabbi of the Jews, walking arm in arm”. Benjamin Franklin, though at 82 too sick to attend the parade, watched as it passed beneath his window. He had overseen, with the chair of the committee on arrangements, Francis Hopkinson, who was also a signer of the Declaration of Independence, “the clergy of almost every denomination united in charity and brotherly love”. This was nowhere more evident than when, at the end of the parade where people gathered at tables heaped with food and drink, the Jewish Patriots were escorted to their own separate table of kosher food.

Benjamin Rush, also a signer of the Declaration of Independence and a delegate to the Pennsylvania ratification convention, on watching the scene, wrote, “The clergy formed a very agreeable part of the procession. They manifested the sense of connection between religion and good government. Pains were taken to connect ministers of the most dissimilar religious principles together, thereby to show the influence of a free government in promoting Christian charity. The Rabbi of the Jews, Jacob Raphael Cohen of Congregation Mikveh Israel, Philadelphia’s only synagogue, locked in arms of two ministers of the gospel was a most delightful sight. There could not have been a more happy emblem contrived of that section of the new Constitution, Article VI, prohibiting religious qualifications for holding office, which opens all its power and offices alike not only to every sect of Christians but to worthy men of every religion”.

Rush noted that the prohibition of a test oath was a true symbol of religious freedom in the Republic. It was a prominent member of Mikveh Israel, Jonas Phillips, who appealed to the Continental Convention as they were drafting the Constitution. In his letter dated September 7, 1787, he voiced his concern that all office-holders in the new government were to be required to swear allegiance over the Christian Bible. He wrote, “to swear and believe that the New Testament was given by divine inspiration is absolutely against the religious principle of a Jew and is against his conscience to take any such oath”. In his eloquent and impassioned letter, he argued that, “during the late contest with England [the Jews] have been foremost in aiding and assisting the States with their lives and fortunes, they have supported the Cause, have bravely fought and bled for liberty which they cannot enjoy”. He wrote the letter for “my children and posterity and for the benefit of all the Israelites throughout the 13 United States of America

Fast-forward to 1938. After the retirement of Minister Louis Washburn, the Christ Church vestry (board) chose Reverend Edward Felix Kloman to take over as the Minister of the congregation. Kloman was an extremely energetic and personable man dedicated to Public Services and the betterment of the community. He immediately made friends with many local businessmen, as the residential neighborhoods near the church had largely disappeared. The Old City section of downtown was very run down in those days, having just endured the Great Depression and still suffering its aftereffects.

Kloman established volunteer groups to take care of the needs of boys, girls, young families, and older residents. The groups welcomed participants from all races and creeds. Kloman believed strongly that the Church should play a role not only in the spiritual development of the neighborhood residents, but also in the general well-being of the neighborhood. He was very much bothered by the filthy streets and unpleasant environment of the Old City area.

In 1941, Kloman, along with a group of local businessmen, formed the Old Christ Church Neighborhood Businessmen’s Association. Foremost among the members was the Treasurer of Mikveh Israel, David Grossman. Grossman was a local businessman who owned a furniture and rug warehouse at Second and Market Streets, where it remains today. Though Grossman was Jewish and was somewhat reluctant at first to serve, he soon became a great friend to Christ Church and did a lot to foster fellowship and cooperation between the church and Mikveh Israel. Grossman served as Secretary of the Association, whose stated purpose was, “the bringing together of the businessmen of the oldest business district in America for the better acquaintance with each other and cooperation for the good of all in the neighborhood”. The group met monthly for lunch and by 1945 had grown to 250 members from all walks of life and a variety of religions.

Aside from the social gatherings, the accomplishments of the Association included cleaning the streets, finding jobs for the unemployed, co-signing loans for those in need, and raising money for the war effort. They increased direct contributions from their district as well as raising the sale of war bonds. Since the effort was led by businessmen of all faiths, it did much to encourage participation in other church efforts in the area.

Largely in response to the atrocities committed by the Nazis in World War II, Kloman reached out to the Jewish Community, many of whom were already friends of Christ Church through their membership in the Neighborhood Businessmen’s Association. He established a special and long-lasting friendship with Mikveh Israel. Every year, on Armistice Day, the Association would sponsor a “prayer for peace”, led jointly by Kloman and Reverend David Jessurun Cardozo, Minister of Mikveh Israel. In 1943, Kloman, along with David Grossman, Rev. Cardozo, and other members of both institutions who were active in the Association came together to establish an annual Fellowship Dinner that is alternately hosted by Christ Church and Mikveh Israel to this day.

Mikveh Israel began its effort in the 1950’s to move from its location at Broad and York Streets to its present location on Independence Mall. In 1961, it officially announced that would move to Center City, and established a building fund to raise money for the new synagogue building. The very first contributor to the fund was Christ Church, who donated $1,000 in May, 1961, presented at the annual Fellowship Dinner, held to commemorate and celebrate the close friendship between these two great and historical Philadelphia institutions.

Bibliography

- Wolf, Edwin, II, and Maxwell Whiteman, The History of the Jews of Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the Age of Jackson. 1957

- Gough, Deborah Mathias, Christ Church, Philadelphia, The Nation’s Church in a Changing City, 1995

- Jaher, Frederic Cople, The Jews and the Nation, Revolution, Emancipation, State Formation and the Liberal Paradigm in America and France, 2002

- Henry Samuel Morais, The Jews of Philadelphia, 1894

- Wikipedia

Commodore Uriah Phillips Levy (1792-1862)

There have been many Jews in the United States Armed Forces and many Jewish heroes in all of America’s wars. Many members of Mikveh Israel served with distinction throughout the history of the United States, with many of them making the ultimate sacrifice in service to their country. Perhaps the most famous of all of them, though, was Uriah Phillips Levy, the first Jewish Commodore in the United States Navy.

Uriah Phillips Levy was born on April 22, 1792 (30 Nissan 5552), and though the country itself had just won its independence 8 years before his birth, his American roots ran deep. Uriah was the grandson of Jonas Philips, who was instrumental in the construction of the first synagogue building of Mikveh Israel, solidifying the congregation and serving as Parnas at the time of its dedication.

Jonas Phillips was born in 1735 in Prussia, though of Spanish descent, and arrived in Philadelphia via Charleston, New York, and London, in 1762 where he married Rebecca Mendes Machado, the daughter of a former Hazan of Shearith Israel Rev. David Mendes Machado. Rebecca was only 16 years old at the time. It is told that George Washington attended and danced at their wedding in Plymouth Meeting, PA, being listed among the guests as “a planter from Virginia”.

Jonas failed in his first few attempts at business, first in retail and then as an auctioneer, and had to resort to performing duties as a Shohet (ritual slaughterer) for Congregation Shearith Israel in order to feed his growing family. Eventually, he would have 21 children, almost all of them surviving to adulthood and most of them becoming prominent members and leaders of Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, Shearith Israel in New York and the secular communities in both cities. After New York proved to be a difficult place for Jonas to become successful, he finally moved the family permanently to Philadelphia in 1774, where opportunity was abundant and success came to him more easily. He went into the dry goods business and eventually became the second richest Jew in Philadelphia, according to city records.

Jonas Phillips was an ardent patriot and strong believer in the American cause. He was also a proud Jew who publically advocated for the rights of his brethren and led his congregation by example. This was a strong influence on his grandson Uriah with whom he was very close, and which guided and strengthened the young man during his entire lifetime, where he faced adversity through anti-Semitism and jealous rivalry.

In 1787 Jonas Phillips’ daughter Rachel, whose twin sister had died in infancy, married Michael Levy. Their wedding was an elaborate one which is described in detail in a letter written by Dr. Benjamin Rush to his wife. This is the only known surviving written description of a Jewish wedding from the 18th century. Not much is known of Michael Levy. Many stories were told by his grandson and Uriah’s nephew, Jefferson Monroe Levy, about how Michael descended from Asser Levy, who was one of the original 23 Jews to land in New Amsterdam (later New York) in 1654, but these stories have long since been disproved. We know that Michael Levy was a charter member of the German Ashkenazic congregation Rodeph Shalom in 1802, and therefore was very unlikely to have descended from the prominent families of the Spanish and Portuguese congregations. He was born of a German family in London in 1755, and likely came to America, possibly Virginia, when he was about 10 years old. He did serve in the American army during the Revolution. His profession was making and selling clocks and watches.

In 1770, Jonas Phillips had been a signer and strong supporter of the New York Non-Importation Agreement. In 1776, when the British occupied Manhattan, Phillips used his influence to close down Shearith Israel rather than continue under the British. Phillips himself had already removed his wife and 15 children to Philadelphia and many of the members of the New York Congregation followed him there. In 1778, Phillips joined the militia in Philadelphia, enlisting as a private under Colonel Bradford. After his service, he supplied the continental army with dry goods, food items, and other needed materials. Following the war, he appealed to President Washington and the Continental Convention drafting the new Constitution of the United States in a letter dated September 7, 1787. His concern was that all office-holders in the new government were to be required to swear allegiance over the Christian Bible. He writes, “to swear and believe that the New Testament was given by divine inspiration is absolutely against the religious principle of a Jew and is against his conscience to take any such oath”. In his eloquent and impassioned letter, he argues that, “during the late contest with England [the Jews] have been foremost in aiding and assisting the States with their lives and fortunes, they have supported the Cause, have bravely fought and bled for liberty which they cannot enjoy”. He wrote the letter for “my children and posterity and for the benefit of all the Israelites throughout the 13 United States of America”.

Against this backdrop, and with a strong guiding influence from his grandfather, Jonas Phillips, Uriah Phillips Levy began his long and successful service to his country and his people. He was drawn to the sea from a very early age, spending a lot of time on the docks of Philadelphia watching the great sailing ships and learning their names and flags as they came in and out of port, loading and unloading their cargo. In 1802, at the age of 10, Uriah ran away from home in the middle of the night to join the trading ship New Jerusalem as a cabin boy. He accepted a 2-year appointment and returned to his family and synagogue just in time for his Bar Mitzvah at Mikveh Israel. After trying and failing to convince the young Uriah to join the family business in retail trade, Uriah’s father in 1806 apprenticed him for four years to one of Philadelphia’s leading ship-owners and a close family friend, John Coultron. Uriah served as a seaman on the schooner Rittenhouse. In 1807, President Jefferson imposed an embargo on all trade with Europe, idling the ships and leaving nothing for Uriah to do. Mr. Coultron took this opportunity to send his young apprentice to a school for navigation led by an ex-lieutenant of the British Navy. When the embargo was lifted, Uriah was off again to sea with far more skills and maturity than before.

By the time he was 18, Uriah had already made several profitable voyages, serving in all of the different capacities during his apprenticeship including cabin boy, ordinary and able-bodied seaman, boatswain, third, second, and first mates, and captain. By the age of 19, Uriah had earned enough money to purchase a one-third interest in a trading ship, the new schooner called the George Washington, named for the first names of his two partners George Mesoncourt and Washington Garrison. When not at sea, Levy was very careful to carry his certification of American citizenship, as British impressment gangs prowled the city looking for young men to force into service in the British Navy. These “protection papers” were usually enough to thwart impressment, so Uriah wasn’t worried when a squad of British marines from the Vermyra approached him. On showing them his credentials, they remarked “You don’t look like an American. You look like a Jew.” Uriah Levy replied, “I am an American and a Jew.” After an insulting remark, the hot-headed Levy displayed the high-handed defensive spirit and refusal to be denigrated that shaped his stormy career throughout his life. He was pressed into service against his will and forced to serve on the Vermyra for a month before he was released. During that time, the commander of the ship, recognizing Uriah’s skills and spirit, repeatedly demanded that Levy join the British Navy. Levy refused, stating “Sir, I cannot take the oath. I am an American and cannot swear allegiance to your king. And I am a Hebrew and do not swear on your testament, or with my head uncovered.” Finally, after an audience with the British Naval Commander in Jamaica, his papers were deemed to be in order and he was released on the condition that he find his own way home.

On one of his first trips commanding the George Washington, Levy picked up a cargo of corn which he sailed to the Canary Islands and sold for 2,500 Spanish dollars and fourteen cases of Teneriffe Canary wine. On his way back to the States, his crew mutinied, stealing the ship, the money and the cargo. Levy barely escaped with his life. Using another ship and determined to bring the mutineers to justice, he hunted them down, finally finding and overtaking them in the Caribbean. He brought them back to Boston, where the leader was hanged and an accomplice received a life sentence.

By the time he arrived home in 1812, the United States had declared war, for the second time, against Great Britain. Levy, barely 20 years old, chose to serve his country in the war over a lucrative career as a privateer. He chose to apply for a commission as a sailing master over the more usual entry as a midshipman. The sailing master handled all aspects of navigation and during sea battles took over the operation of the ship while the captain directed the fighting. Later he explained his choice, saying “I sought this particular position in the belief that my nautical education and experience would enable me to render greater service to my country”. His commission from President James Madison came through in October, 1812, and he was assigned to the USS Argus, where his first assignment was to transport William H. Crawford, the new minister to France, to his post in order to entreat the French for support during the war. After depositing Crawford safely in France, the Argus began a short but very successful run as “the dreaded ghost ship” that attacked and destroyed much larger British ships in the Channel. Levy received a temporary promotion to Lieutenant and assigned the task of boarding, destroying, or commandeering the captured ships. While transporting a valuable ship, the Betty, to a French port, the Argus was finally overpowered and destroyed, with the captain and most of the crew killed. Meanwhile, the unarmed Betty was captured, and Levy spent the duration of the war in prison until he was released in a prisoner exchange after the war.

Levy was assigned to the USS Franklin in 1816. He was met there with prejudice and ostracism. Soon afterwards, while dancing in full uniform at the Patriot’s Ball in Philadelphia, a somewhat drunk Lieutenant William Potter bumped Levy on the dance floor. After a second and then a third forceful collision, Levy turned and slapped Potter across the face. Enraged, Potter cursed Levy as a Jew, to which Levy responded, “That I am a Jew, I neither deny nor regret”. The two were separated and Potter led away. The following morning, Levy received a formal challenge to a duel. Levy was not anxious to fight a man over a dance-floor incident and offered to shake hands and forget the whole thing. Potter refused and they agreed to a pistol duel in a meadow in New Jersey, as dueling had been outlawed in Pennsylvania. Asked by the judge if he had anything to say, Levy asked permission to utter a prayer in Hebrew, the Shema, and then said, “I also wish to state that, although I am a crack shot, I shall not fire at my opponent. I suggest it would be wiser if this ridiculous affair be abandoned”, to which Potter replied, “Coward!”. Levy gave Potter the first shot, which went wide. Levy then simply pointed his pistol in the air and fired. Potter reloaded a second round and fired, again wide of the mark. Levy reloaded and again fired into the air. A third and fourth shot missed Levy, each time returned with harmless shots into the air. Finally, a fifth shot nicked Levy’s ear. After Potter loaded for a sixth shot, Uriah took careful aim and fired into Potters chest, killing him instantly. The affair created quite a stir in Philadelphia and the press who praised Levy for his honor. He was acquitted during his subsequent court martial. Judged to not have been the provocateur nor the aggressor, his case was dismissed. He was also acquitted by a jury in the civil indictment brought against him.

Following this incident, Levy received his official promotion to Lieutenant. The jealousy and prejudice expressed both by those passed over in favor of Levy and among those whose ranks he joined began a career of ceaseless persecution and undeserved punishment simply because he was a Jew. Back in Philadelphia, a friend took him aside and strongly advised Uriah not to pursue a career in the Navy. He warned him that though nine of ten commanding officers wouldn’t care that Levy is Jewish, the tenth will make his life hell. According to his memoirs, Levy responded, “What will be the future of our Navy if others such as I refuse to serve because of the prejudices of a few? There will be other Hebrews, in times to come, of whom America will have need. By serving myself, I will help give them a chance to serve”.

Three years later, his troubles resumed while serving as the third lieutenant aboard the United States. On presenting himself for duty, he was rejected twice by the captain on account of his being a Jew. The commodore had to get involved to secure the position. It was aboard the United States that Uriah witnessed his first flogging. He was so horrified that he worked for the rest of his career to end the practice. After getting into a fight with another lieutenant over a small issue, the vindictive captain ordered a court martial and had Levy dismissed from the Navy. President Monroe reviewed the case and reversed the decision. But by the time this had happened, Levy had another fight over an even more trivial matter and now faced court martial number three. In his defense, he accused his fellow officers of anti-Semitism. He made a long and impassioned speech complaining of being unfairly treated because of his faith. The court was unsympathetic and returned a verdict of guilty and dismissed him from the Navy in disgrace. After spending a couple of years wandering around Europe and living for a time in Paris, he finally returned home to some astonishing news. After two years, his case finally reached President Monroe’s desk for review. Monroe decided that Levy’s offense was not sufficient for dismissal and the suspension he already served was punishment enough, and he was restored to his position. A fourth court martial over another verbal volley of insults resulted in a draw, both the accuser and the accused being reprimanded.

In 1825, Uriah was serving as second lieutenant on the Cyane, which was stationed off the coast of Brazil. While the ship was in port for repairs, Levy witnessed an American seaman being seized by a Brazilian press-gang. The young man called for help. When Levy’s midshipman stepped in to rescue the boy, he was attacked by the Brazilian officer who slashed at him with his saber. Levy stepped in and received the blow, saving the midshipman’s life while incurring slashes to his wrist and his rib. The following day, he received a visit from the Emperor of Brazil Dom Pedro. Pedro had been so impressed with Levy’s bravery that he ordered that Americans were not to be ever again pressed into service of the Brazilian Navy. He then offered Levy a commission in the Brazilian Imperial Navy on its newest ship that had just been built in the United States. Levy politely refused, telling the Emperor, “I would rather serve as a cabin boy in the United States Navy than hold the rank of Admiral in any other service in the world”. Levy became very popular, however his views on flogging were not. He used humiliation as an alternative punishment, which was not appreciated by his fellow officers.

Once again, he exchanged words with another officer after his honor, integrity and religion were insulted. He responded by challenging the officer to a duel. A fifth court martial resulted, ending in a public reprimand for Levy. He counter-sued and won, leaving the other officer suspended for a year. This did not endear him to his fellow officers who ostracized and ignored him. Bitter and dejected, Levy asked for and received a six month leave of absence. His commanding officer wryly offered to extend the leave indefinitely, to which Levy inquired if this was because he was a Jew. The officer replied that it was. Levy moved to New York City, where he decided to invest his Navy savings in real estate. Within four years he had become very wealthy. In 1833, he commissioned Pierre Jean David d’Angers to sculpt a statue of Thomas Jefferson, whom Levy considered “one of the greatest men in history”. Levy had the statue delivered to the Capitol with a letter, and after some discussion, Congress finally accepted the gift and placed it in the Rotunda where it stands today.

Jefferson had died on July 4, 1826 on the 50th anniversary of the United States. His house, Monticello, and its grounds went to his daughter Martha. After two years, she couldn’t afford the upkeep and offered it for sale. No takers were forthcoming at her asking price of $71,000, and she finally ended up selling it for a mere $7,000 to a man who intended to use the land for growing silkworms. After that venture proved unsuccessful, he left the property abandoned, looted and neglected. Levy made a pilgrimage to the property in 1834 and finding it so run-down, purchased it for $2,700, resolving to restore it to its former glory. As he did so, he moved his mother Rachel Levy to live there permanently, and himself spent summers restoring the house and property. Rachel is buried on the path to the house. In his will, Levy left the house to the People of the United States, or failing that, to the State of Virginia. As it turned out, neither was interested in taking it, so after some time Uriah’s nephew, Congressman Jefferson Monroe Levy, bought out the other heirs and once again restored the property, searching throughout the United States for authentic Jefferson furniture to fill the house. In 1923, Jefferson Levy sold the house and property to the Monticello foundation.

Meanwhile, Levy had been petitioning the Navy throughout his leave requesting duty. Finally in 1837, he was promoted to Commander after 20 years as lieutenant. The following year he received orders to take command of the Vandalia. He took this opportunity to eliminate the practice of flogging in favor of new rules for conduct and discipline. As a result of an incident involving a humiliating punishment given to one of his men, he was again court martialed for a sixth time. Once again, he was dismissed from the Navy amid much discrimination on the part of the court. This time, it was President Tyler who reversed the decision, deciding that the ruling against Levy had not been made for the good of the service. He agreed with Levy that flogging should only be used as a last resort and avoided whenever possible. Upon the recommendation of the President, Levy was promoted to Captain. While petitioning for an active duty assignment, Levy devoted time to lobbying the flogging issue and writing pamphlets in support of his cause. Despite opposition from the Navy, an anti-flogging rider was attached to the Naval appropriations bill of 1850 and the practice of flogging was finally outlawed in 1862.

In 1855, after petitioning for years for an assignment, Levy, along with 200 other officers, were dismissed from the Navy. Levy was enraged, suspecting discrimination once again and hired a lawyer, Benjamin Butler, who wrote a letter to petition congress to restore Levy to his post. Congress convened a Court of Inquiry in 1857, and the following year Levy along with about a third of the other officers were restored to active duty. Four months later, Levy was given orders to take command of the Macedonian in the Mediterranean squadron, and given the rank of Commodore.

Uriah P. Levy died on March 22, 1862 (Adar II 20, 5622). The navy honored him by launching the USS Levy during World War II. At a ceremony on Friday December 16, 2011 attended by hundreds, a 6-foot high bronze statue of Uriah P. Levy was dedicated at Mikveh Israel. The statue, designed and sculpted by Gregory Pototsky, sits on the Fifth St. lawn facing Independence Mall. The statue and its dedication were made possible by Navy Captain Gary “Yuri” Tabach and Joshua Landes, in association with the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs. Landes served as the master of ceremonies for the dedication. Addresses were given by Landes’ father, Retired Rear Admiral and Rabbi Emeritus of Congregation Beth Sholom, Aaron Landes, John Lehman, former Secretary of the Navy, Rear Admiral Herman A. Shelanski, and a number of other distinguished speakers. A video of the dedication ceremony can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZLWBo-IrRiA.

Uriah Phillips Levy was a proud, determined, forthright, and some would even argue pugnacious man. He was fiercely patriotic and loyal to his country, while at the same time proud of his people, his religion, and his heritage. He was ready at all times to sacrifice his life and his honor in defense of his country or his religion. These qualities were instilled in him from a very early age by his family and he spent his entire life fighting injustice, intolerance, and discrimination. As Levy himself put it, “I am an American, a sailor, and a Jew”.

(click image to enlarge)

(click image to enlarge)

Bibliography:

- Americanjewisharchives.org

- Jacob Rader Marcus, Early American Jewry, 1955

- Wolf, Edwin, II, and Maxwell Whiteman. The History of the Jews of Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the Age of Jackson. (1957)

- Melvin I. Urofsky, The Levy Family and Monticello, 1834-1923: Saving Thomas Jefferson’s House, 2001

- Marc Leepson, Saving Monticello, 2001

- Stephen Birmingham, The Grandees: America’s Sephardic Elite, 1997

- Simon Wolf, Biographical Sketch of Commodore Uriah P. Levy, American Jewish Committee, Jewish Publication Society, 1903

- Rachel Pollack, Biographical Note to the Uriah P. Levy Collection, American Jewish Historical Society, 2004

- Henry Samuel Morais, The Jews of Philadelphia, 1894

- James Morris Morgan, An American Forerunner of Dreyfus, The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, 1899.

- Jewishsphere.com, Jewish War Heroes from 1775, 2009

- Fifty years’ work of the Hebrew Education Society of Philadelphia: 1848-1898

- Ellen M. Umansky & Dianne Ashton, Four Centuries of Jewish Women’s Spirituality: A Sourcebook, 2009

- Erika Piola, Jewish Women’s Archive, Jewish Women, A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia

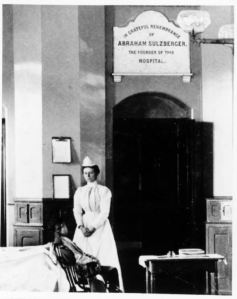

Abraham Sulzberger and the Jewish Hospital

This week we remember the Hashcabah of our dear friend and lifetime member of Mikveh Israel, Berthold Levy who passed away a couple of years ago at the age of 97. Levy was the great grandson of Abraham Sulzberger, who was the first of Bert’s ancestors to come to Philadelphia and begin a long legacy of outstanding and influential members of Mikveh Israel, the wider Jewish community in Philadelphia, and the broader secular society in Philadelphia in general.

Abraham Sulzberger was born in Heidelsheim in Baden, Germany on May 20, 1810. His father, Solomon (Meshullam) Sulzberger, had been a Rabbi there and Abraham followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming a scholar in Jewish texts as well as serving as Hazan, reader, shohet (slaughterer) and teacher in his local congregation. He married Sophia Einstein and had six children, including the famous Judge Mayer Sulzberger who was born on June 22, 1843, and was destined to be the most prominent and influential Philadelphia Jew of his generation, and in 1894 was the first Jew to sit as a judge of the Court of Common Pleas.

During the uprising of 1848 in Germany there were reprisals against the Jews, and Sulzberger decided to relocate his family to America. His older brother Leopold had already settled in Philadelphia in 1838, so Abraham prepared the family for the long journey to join him there. The journey began with a trek that lasted for months across Germany and France in a wagon, eventually reaching the French port city of Le Havre. There they boarded a transatlantic steamer called the Splendid, and arrived in New York Harbor on August 11, 1849. From there they made their way to Philadelphia and established themselves in the city and joined Mikveh Israel. The following year, Sulzberger was one of 8 charter members who founded the Har Sinai Lodge of District No. 3 of the B’nai B’rith. Sulzberger served as its president for the next 25 years.

During the Civil War, Rev. Isaac Leeser, the former Minister of Mikveh Israel, was very concerned about the wounded Jewish soldiers in the army hospitals. He obtained a hospital pass from his friend General Charles Collis, who was married to Septima Levy, formerly of Charleston. Sulzberger would accompany Leeser on hospital visits to the Jewish wounded. It was just after the Battle of Gettysburg in early July of 1863 that Sulzberger and Leeser began discussing a plan for a hospital. By this time, Leeser had already separated from Mikveh Israel on somewhat unfriendly terms and had become the minister of a new congregation Beth El-Emeth. Because Leeser was a major force behind this initiative, Mikveh Israel was reluctant to work directly with him on the project.

They turned next to the new Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel, confident that they find support for the project given the many denominational Christian hospitals that had been built over the previous generation by the Catholic (St. Josephs) and Episcopal Churches, and by the German Christian population (Lankenau). Keneseth Israel was founded in 1847 as an Orthodox synagogue, and in the years just before the first synagogue building was dedicated in 1854, Abraham Sulzberger had helped the congregation as one of the hazanim (readers). Both Rev. Isaac Leeser and Rev. Sabato Morais had taken part in the dedication ceremony of the new building. Within a few years however, the congregation, under the leadership of Rev. L. Naumburg, adopted some of the “innovations” of the Reform Movement such as a mixed choir and the introduction of an organ into the service. Under the leadership of Rev. Dr. Solomon Deutch, who became the Rabbi in 1857, and Rev. Dr. David Einhorn who took over in 1861, the congregation fully became a Reform Congregation. As such, the congregation objected to the strict observance of Kashrut insisted by Sulzberger and Leeser for the new hospital and refused to help.

Out of options with the religious institutions, they turned to the B’nai B’rith. Sulzberger was the past President of the local lodge, and Leeser, after initially resisting and opposing the order during its early years as secret society, had joined and moved up through the ranks to a top influential position as Vice-President of the Elim Lodge. During the annual meeting of the Grand Lodge No. 3 of the B’nai B’rith on August 14, 1864, Sulzberger, in calling attention to the fact that three Jews within the previous six months had died in various area Christian hospitals without the option of being fed kosher food or being administered Jewish rites, offered resolutions asking for the appointment of a committee to consider the subject of organizing a Jewish Hospital. He further noted that both New York City, Cincinnati, and the larger cities in Europe had seen the need and built hospitals for their Jewish populations. It was a discredit, they argued, to the Jewish population of Philadelphia to allow their brethren to be cared for and possibly die in the care of strangers who did not understand or approve of the obligations of Jewish law.

That committee was established and included Sulzberger, Rev. Isaac Leeser, Samuel Weil and others. Within a few days a circular was sent to every B’nai B’rith Lodge and all of the congregations and Jewish societies in the area requesting appointments for committees. On December 4, the first meeting of this joint convention was held during which a plan was prepared, and a constitution and by-laws were framed and presented. On Sunday February 19th, 1865, these were ratified by a large meeting of the area Jews at a meeting held at the National Guard’s Hall on Race Street below Sixth. Officers and managers were appointed, including President Alfred T. Jones, Vice President Isadore Binswanger, Treasurer Samuel Weil, and Secretary Mayer Sulzberger. Abraham Sulzberger’s home at 977 North Marshall Street became the temporary headquarters of the provisional committee for the hospital.

The Association was incorporated on September 23, 1865 and a lot was soon purchased at 56th Street and Haverford Road in West Philadelphia for $19,625. The Jewish Hospital opened the on August 6, 1866 along with a home for the aged. It started with 22 beds and linens donated by philanthropist Moses Rosenbach. During the first year 71 patients were treated and 5 people were admitted to the old-age home. In 1873, the hospital moved to greatly expanded facilities at Old York Road and Olney Avenue. In 1952, after merging with Northern Liberties Hospital and Mount Sinai Hospital to form a single medical center, it evolved into the Albert Einstein Medical Center. It was very appropriate that Einstein granted permission to use his name for the non-profit organization, as Abraham Sulzberger’s wife Sophia was an ancestor of Albert Einstein.

- www.geni.com

- www.ancestry.com

- Wolf, Edwin, II, and Maxwell Whiteman. The History of the Jews of Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the Age of Jackson. 1957

- Lance J. Sussman, Isaac Leeser and the Making of American Judaism, 1995

- Maxwell Whiteman, Mankind and Medicine: The making of Albert Einstein Medical Center, 1966

- Robert P. Swierenga, The Forerunners: Dutch Jewry in the North American Diaspora, 1994

- Henry Samuel Morais, The Jews of Philadelphia, 1894

- Arthur Kiron, The Mayer Sulzberger Collection, Biography, Library of the Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, 1994

- Hasia R. Diner, A New Promised Land: A History of Jews in America, 2000

- Fifty Years’ Work of the Hebrew Education Society of Philadelphia 1848-1898

- Samuel Hazard, Hazard’s United States Commercial and Statistical Register, Volume 3, Philadelphia, 1841

- Wikipedia

Ellen Phillips (1820-1891)

This week we remember the Hashcabah of Ellen Phillips, who died on February 2, 1891 (24 Shebat 5651). Ms. Phillips descended from one of the original families of Mikveh Israel, and a long line of illustrious and important leaders in the Jewish community of Philadelphia.

She was born on October 30, 1820, the tenth of eleven children of Zalegman Phillips and Arabella Solomons. Nine of the eleven children lived to adulthood, though only three married and had children themselves. Ellen herself never married, which was the case with most of her cousins, nieces and nephews.

Those of her relatives who did have children, tended to have very large families. Her father, Zalegman, was one of 21 children of Jonas Phillips and Rebecca Machado. Her aunt Rachel Phillips married Michael Levy and had 10 children, one of whom was Uriah Phillips Levy, the famous Commodore of the US Navy, noted for helping to end the practice of flogging in the Navy, as well as for buying and restoring Monticello, the former home of President Thomas Jefferson. Her uncle Naphtali Phillips, who lived to be 97 years old, had 16 children, 10 with his first wife Rachel Seixas and, after she passed away, he married her cousin Esther Seixas and had 6 more children. Her uncle Benjamin Phillips had 9 children.

Ellen Phillips grew up as part of the elite leadership of Mikveh Israel, and it was an integral part of her entire life. Her grandfather Jonas Phillips was the Parnas during the construction of the first synagogue building in 1782. Her uncle Naphtali also served a term as Parnas. Her father Zalegman began his second term as Parnas when Ellen was 2 years old, and held that position until she was 14. He died 5 years later when she was only 19. Her mother had died when she was 11.

Zalegman Philips graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1795, and was admitted to the Philadelphia Bar in 1799. Over the next few years, he became one of the best criminal lawyers in Philadelphia; he had a large clientele and amassed great wealth. In addition to his work for the congregation, he was very active in communal and charitable institutions. All of his children followed in his footsteps, including Ellen. She was left with substantial wealth and dedicated her life to founding and leading charitable and educational organizations in the City of Philadelphia.

It was a tight-knit group of elite Victorian women who worshipped together at Mikveh Israel, socializing together, and joining together in their philanthropic endeavors. The group included Rebecca Gratz, Luisa B, Hart, Simha Peixotto, Mary M. Cohen, and Ellen Phillips among others. They did so with the help and hard work of the Rabbis of Mikveh Israel, first Rev. Isaac Leeser followed by Rev. Sabato Morais, who between them served the congregation and the Jewish community of Philadelphia from 1829 to 1897.

Ms. Phillips was a warm, generous, and hard-working woman. She was kind, pleasant and unostentatious in her manners, and humble in her ways. Her satisfaction in life came from helping and educating others, imparting on them her great piety, deep knowledge of Judaism and sincere love and gratitude toward the Almighty. Ms. Phillips spent her entire career ministering to, and aiding and supporting the poor, providing the means for Jewish education of the youth, and working for the well-being of both young and old. She gave tens of thousands of dollars to support the institutions to which she also gave her physical labor and sharp intellect, not the least was supporting the Divine Service and congregational activities at Mikveh Israel.

Ms. Phillips was one of the original founders and teachers of the Hebrew Sunday School Society, the brainchild of Rebecca Gratz. Ms. Phillips helped write its constitution, and working together with Ms. Gratz and Luisa B. Hart, launched the organization on March 4, 1838. They were assisted by Rev. Isaac Leeser, who taught classes and wrote a much of the material used for the curriculum. The mission of the school was to provide supplementary religious education to all Jewish children. Rebecca Gratz served as its superintendent for the first 26 years, succeeded by Ms. Hart. Ellen Phillips assumed the helm as superintendent in 1871. Ms. Phillips recognized that with all of the new Jewish immigrants pouring into the city, changes and improvements would be necessary to accommodate the new students. She divided the school into Northern and Southern schools. Rev. Sabato Morais was deeply devoted to the interests of the school during the years Ms. Phillips ran the school, and was one of the primary teachers.

When she passed away on February 2, 1891, Ms. Phillips bequeathed over $110,000 (worth over $2.5Million today) to different secular and religious institutions. She bequeathed $15,000 to the Hebrew Education Society to continue her lifetime of service. A bronze tablet in her memory was placed in the main hall. She also left money to the Society Esrath Nashim (Helping Women), an organization she had donated much time and money to during her lifetime. In return, they honored her memory in a meeting in June 1891, resolving to name the first bed in their newly expanded Jewish Maternity Home, at 534 Spruce St, Philadelphia, in her memory with the following words:

Resolved – That inasmuch as her character was outwardly modest and retiring, so shall the exterior of the Home be unostentatious; as her life was full of beauty and imbued with charity toward all humanity, so shall the Home be fitted with every appliance for the relief and sustenance of its beneficiaries; and, as she was truly a pious and observing Jewess, so may we conduct our house, in the observance of those laws laid down for the benefit and blessing of all Israel.

Finally, they resolved that a copy of the resolutions be sent to Ellen’s surviving sister Miss Emily Phillips, and also published in the Jewish Exponent.

Ms. Phillips also left money in her will to the Jewish Theological Seminary, the Young Women’s Union, the American Philosophical Society and the Fairmount Park Art Gallery.

Bibliography

- Americanjewisharchives.org

- Jacob Rader Marcus, The American Jewish Woman: A Documentary History, 1981

- Wolf, Edwin, II, and Maxwell Whiteman. The History of the Jews of Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the Age of Jackson. (1957)

- American Jewish Historical Society Quarterly, Volume 11. Cyrus Adler, President, 1903

- Henry Samuel Morais, The Jews of Philadelphia, 1894

- Arthur Kiron, The Professionalization of Wisdom: The Legacy of Dropsie College and Its Library

- Fifty years’ work of the Hebrew Education Society of Philadelphia: 1848-1898

- Ellen M. Umansky & Dianne Ashton, Four Centuries of Jewish Women’s Spirituality: A Sourcebook, 2009

- Erika Piola, Jewish Women’s Archive, Jewish Women, A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia

Reverend Abraham Lopes Cardozo (1914-2006)

This week we remember Hazzan Abraham Lopes Cardozo. Rev. Cardozo was Hazzan of Shearith Israel From 1946 until his retirement in 1984. He was the embodiment of the Western Sephardic liturgical tradition that was brought to North America from Amsterdam via Recife, Montreal, and the Caribbean, among other places. He was the spiritual and musical teacher of the present Rabbi of Mikveh Israel, R. Albert Gabbai, bringing some of his rich influence to Philadelphia. Rabbi Gabbai would often invite Rev. Cardozo to come to Philadelphia for High Holidays and other occasions after his retirement.

Rev. Cardozo was born on September 27, 1914. His father, Joseph Lopes Cardozo, was the leader of the boys choir at the Spanish and Portuguese synagogue in Amsterdam. He was also a violinist, and along with Cardozo and his two brothers, the foursome formed a band that played at various gatherings and communal holiday celebrations. They all could play keyboards and also string, reed, and brass instruments. Of course, Bram, as Abraham Cardozo was known, grew up completely immersed in music of all kinds and had a natural talent. He even played piano as a toddler. As he grew, he could play any piece he heard by ear.

At 18, Bram Cardozo earned his degree as a Hebrew teacher from the Ets Haim Seminary in Amsterdam. A few years later in 1938, he answered an advertisement for a Hazzan who was needed for a congregation in Surinam, Zedek Ve-Shalom. The ad was placed by his future father-in-law, Judah Robles, who was Parnas of the synagogue at the time. After much deliberation over different candidates, Bram Cardozo was chosen because of his credentials and also because the salary, paid for by the Dutch government, and living conditions were appropriate for a single young man. He arrived in Paramaribo, Suriname on September 9, 1939. As it turned out, this appointment saved his life. All of the rest of his family in Holland perished in the Holocaust. Throughout his life, he observed Tisha B’Ab as the Nahalah (anniversary) for all of his relatives that were murdered, as this is the national Jewish day of mourning.

In 1945, Rev. Cardozo took a six-month leave of absence from his job as Hazzan in Suriname, and headed to New York. The Suriname community was declining in the wake of the war, and he wanted to expand his horizons and look for other opportunities. New York City provided the perfect vibrant Jewish community for him to spread his wings. Of course, Rev. Cardozo found his way to the Spanish and Portuguese synagogue, Shearith Israel. There, as a visiting Hazzan of a sister synagogue, he was invited to lead services. This led to an offer to join the congregational staff as an Assistant Hazzan, which he accepted. After returning to Suriname to give notice to a very disappointed Mr. Robles, be began his long tenure at Shearith Israel on January 1, 1946.

Immediately on starting as Hazzan, Rev. Cardozo reunited with the daughter of his former Parnas in Suriname, Irma Miriam Robles, who was working in New York and attending Shearith Israel regularly. They shared many of the same friends and grew close over the next few years. In December of 1950 they became engaged, and had a beautiful wedding on March 11, 1951, officiated by Rev. Dr. David de Sola Pool of Shearith Israel, assistant minister Rev. Dr. Louis Gerstein, and Rev. David Jessurun Cardozo, the Rabbi of sister congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia. Of course, the first piece of furniture they acquired for their new home was a piano – a Baldwin Acrosonic upright. The Cardozos had two daughters, Debby and Judy born in 1952 and 1955.

Rev. Cardozo was devoted to and strictly upheld the Spanish and Portuguese minhag, though in his private life he also appreciated other traditions. In many ways he was a living bridge between the Old World represented by the Amsterdam Sephardi community which was made up of descendants of refugees from the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal, and the New World in the first congregation in America. As the Amsterdam community was being decimated by the Nazis, Cardozo escaped just in time and continued the traditions in the New World. Rabbi Marc Angel, long time Rabbi of Shearith Israel speaking at his funeral in 2006, said that Rev. Cardozo was an ember that survived the ashes of the Holocaust.

Rev. Cardozo’s passion in life was Hazzanut, and there was nothing he enjoyed more than leading the congregation in prayer using the tunes he knew and loved so well. Sadly though, as he was required to strictly maintain the Shearith Israel minhag, he was prevented from introducing some of the other Spanish and Portuguese melodies from the mother synagogue in his native Amsterdam that he so eagerly wanted to keep alive. Though he was not given the title of Minister of the congregation until late in life, he performed weddings, funerals, and gave eloquent eulogies.

After he retired, he wrote two books, each with an accompanying CD of music. The first was Sephardic Songs of Praise, followed a couple of years later by Selected Sephardic Chants. Many of his friends collaborated to present a petition to Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands, nominating Rev. Cardozo for the title of “Knight in the Order of Orange Nassau” for his service during World War II, his preserving the traditions and minhag as practiced for hundreds of years in Amsterdam, and his loyal and proud representation of the Dutch Jewish Heritage. He was officially knighted in the year 2000.

In March 2005, Rev. Cardozo fell and broke his hip. Unfortunately, he never fully recovered and passed away on February 21, 2006 (23 Shebat 5766) at the age of 92. Hundreds of people came to the synagogue to attend his funeral and pay their respects to this great and humble man and leader of the community for 60 years. Eulogies were given by dozens of leaders, rabbis, colleagues, close friends and family. Rabbi Angel led the hakafot (circuits) around the coffin in a very moving ceremony, after which the coffin was draped with his Talet (prayer shawl).

I just want to share one very small personal anecdote. I used to lead the Friday night Shabbat service at Mikveh Israel. One time when Rev. Cardozo was visiting for Shabbat at the invitation of Rabbi Gabbai, he led the Friday night service faster than I have ever heard it done. It was so fast, I could hardly follow along. After the service, as I was wishing him a Shabbat Shalom, I remarked on the speed with which he read the service. He replied, with a twinkle in his eye, “they don’t call me the Flying Dutchman for nothing!”.

Bibliography

- Irma Miriam Lopes Cardozo, As I Lived It, 2010

- Shelomo Alfassa, Reverend Abraham Lopes Cardozo z”l, The Jewish Voice – March 3, 2006

- The New York Times, Ari L. Goldman, Published February 23, 2006

- Yedeabraham.com, People Identified on this Site

Manuel Josephson (1729-1796)

This week we remember the Hashcabah of Manuel Josephson, one of the original members of Congregation Mikveh Israel at the time of the construction of the first synagogue building in 1782. Josephson was born in 1729 in Germany, and died on January 30, 1796 (20 Shebat 5556). Josephson married Rachel (Ritzel) Judah, daughter of Baruch and Sarah Helbert Judah in New York City on Lag Lahomer, 15 May 1759.

When he first came to the America, Josephson became a merchant, supplying the armies in the French and Indian War in 1757. He settled in New York and joined Congregation Shearith Israel. Josephson soon became a prominent member of the congregation. Shalom Goldman notes that Josephson “owned the best library of rabbinic texts in colonial times and was well versed in rabbinic Hebrew”. He served as one of the judges on the Shearith Israel bet din (rabbinic court). On many occasions, Josephson articulated religious questions addressed to rabbinic authorities in England and Holland. Occasionally, he also rendered his own halachic decisions. In 1762, Josephson was elected as Parnas of Shearith Israel.

The 1760s and 1770s were times of great contention in Shearith Israel. There were numerous fights and disputes between members and between members and the leadership of the congregation. Much of this has come down to us through history because the synagogue started keeping secret minutes to record the worst of the issues. Some examples include Isaac Pinto, who in 1767 was fined for “abusing” the Parnas. A Shamash was suspended for insubordination. In 1771, a general meeting of the congregation had to be called because the Parnas-elect, Moses Gomez refused to assume his position. Largely, the infighting and questioning of the governing body of the congregation was a reflection of what was going on in the streets of New York and the other major cities in the colonies as the people rejected the authority of the British monarchy.

As the issues escalated, two of the disputes ended up in public civil trials. One of them involved Manuel Josephson, who in 1770 publicly criticized 84 year-old Joseph Simson, who was the father of Josephson’s merchant colleagues Solomon and Sampson Simson. As Howard Rock describes the scene, Josephson berated Simson “because the elder Simson’s prayer shawl was unkempt and because of his flawed speech and unseemly gestures.” The insults flew back and forth with the younger Simson calling into question Josephson’s business practices and his humble origins and scolding him for picking on an old man. In the end, the court found for the synagogue and against Josephson. Incidents, disputes, name-calling, and fights continued this way in the congregation until 1776, when the British occupied Manhattan and the congregation decided to close the synagogue and disperse. Most of the members either joined the military on the side of the colonists or dispersed northward to Newport or south to Philadelphia and Congregation Mikveh Israel. Manuel Josephson was part of the latter group, which also included the Hazan, Gershom Mendes Seixas.

Josephson arrived in Philadelphia as part of the New York contingent and set up shop as a merchant with a store at 144 High Street, later in about 1800 called Market Street. Aside from quickly becoming one of the leaders of Mikveh Israel, he was also held in very high esteem in the general community by Jews and non-Jews alike.

Josephson was a very traditional and observant Jew. In 1784 he petitioned the board of Mikveh Israel asking that a ritual bathhouse (mikvah) be built for the women of the congregation, in order that they observe Jewish law. Accordingly, the mikvah was built in 1786, while Josephson was Parnas of the congregation, and the board placed it under his supervision. Josephson was elected as Parnas in 1785, and served through 1791. His most famous accomplishment, however, came in 1790.

Shortly after the US Constitution was ratified in 1789, George Washington was elected as the first President of the United States. Moses Seixas, the brother of Gershom Mendes Seixas who was the minister of Shearith Israel at the time and was the minister of Mikveh Israel during the war, wrote a beautiful letter to the new President, filled with warmth and eloquence. He famously noted that the new Government of the United States of America gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, and considers all of its citizens of all religions equal under the law. Washington’s famous reply repeated the eloquent words of Seixas and affirmed the equality of the Jews, and declared that America was different from other nations of the world because “All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship”.

This was to be the second of three letters that Washington wrote to different Jewish communities during that year, mainly because of discrimination and infighting among the Jews. Shortly after the inauguration in April 1789, the presidents of the six congregations in the US – New York, Philadelphia, Newport, Charleston, Richmond, and Savanna – agreed to send a joint letter. Then they spent the next year and a half arguing over who would sign it! The original plan called for the letter to be sent from Shearith Israel in New York, as this was originally the capital of the fledgling country. But there were months of delays and meanwhile, Congress moved the capital to Philadelphia in January of 1790.

Then Manuel Josephson, Parnas of Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, offered to write the letter on behalf of the other congregations. However, the Spanish & Portuguese Sephardic elite who dominated the other congregations objected to the Ashkenazic Josephson, of humble Eastern European origins, considering him unworthy to speak for them. A few months passed in which nothing was done, so finally in May, the Savanna congregation, noting and apologizing for the delay in writing, presented a letter to Washington. Washington was gracious in his eloquent reply. In August, Moses Seixas and the Jews of Newport also tired of waiting and presented their own letter, certainly the most famous of the three, along with its often-studied reply.

Finally, in December 1790, Josephson, in a short meeting with Washington, presented a letter from the four remaining congregations from Philadelphia, New York, Charleston, and Richmond. Josephson apologized for the delay in adding their congratulations to those of the rest of the nation. Washington’s reply was shorter than the other two, but was nonetheless warm and appreciative, stating that “The affection of such a people is a treasure beyond the reach of calculation” and conveyed how much pleasure he received from the support and approval of his fellow-citizens. He thanked the Almighty for intervening on behalf of the Americans in the “late glorious revolution”, and promised to work just as hard for the country in times of peace as he did during the war. He closed by saying, “May the same temporal and eternal blessings which you implore for me, rest upon your congregations”.

Manuel Josephson died on 30 January 1796 and is buried in the Mikveh Israel Spruce St. cemetery. His wife, Rachel died on the same Hebrew date, 20 Shebat, a year later and his buried beside him.

Bibliography

- Howard Rock, Haven of Liberty: New York Jews in the New World, 1654-1865, 2012

- Shalom Goldman, God’s Sacred Tongue: Hebrew & the American Imagination, 2004

- Jacob Rader Marcus, The American Jewish Woman: A Documentary History, 1981

- Jeffrey S. Gurock, Orthodox Jews in America, 2009

- Wolf, Edwin, II, and Maxwell Whiteman. The History of the Jews of Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the Age of Jackson. (1957)

- American Jewish Historical Society Quarterly, Volume 11. Cyrus Adler, President, 1903

- Henry Samuel Morais, The Jews of Philadelphia, 1894

- Jonathan Jeremy Goldberg, Jewish Power: Inside the American Jewish Establishment, 1996

Isaac Hyneman (1804-1886)

This week we remember the Hashcabah of Isaac Hyneman. Mr. Hyneman was a prominent member of Mikveh Israel. He was Born in 1804 in Hofgeismar, Hesse-Cassel, Germany and died on January 14, 1886 (8 Shebat, 5646). He came to Philadelphia in the early 1830s. Soon after, he moved to Richmond, Virginia and in 1834 married Adeline Ezekiel, who was born in Philadelphia May 10, 1815, but was at the time living in Richmond, VA. Together they had five sons, Augustus, Leon, Jacob, Herman, and Samuel, all of whom were prominent in the Congregation Mikveh Israel and in the secular community. They lived in Richmond until 1850, when the family moved to Philadelphia. In their adult lives Leon, Jacob, and Samuel lived in Philadelphia, and Augustus and Herman resided in New York.

In 1836, Isaac entered into the dry goods business with his brother-in-law, Adeline’s brother Jacob Ezekiel, under the firm name of Ezekiel & Hyneman. The business was very successful and gave Isaac the resources to give generously of his time and money to many Jewish Educational and Charitable associations in Philadelphia. He was on the Board of Offices of the Hebrew Education Society.

Adeline Hyneman was very active in the affairs of the Jewish community and contributed her time and concern to a number of charitable organizations. She was a manager for the Jewish Foster Home and Orphan Asylum.

Isaac’s son, Herman Naphtali Hyneman, born July 27 1849, was quite an accomplished painter. After studying painting in Germany and France for 8 years, he returned to Philadelphia where he opened an art studio. His works have been displayed in Paris, Philadelphia, and New York City. To this day, several of his paintings are displayed at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the National Academy of Design in NYC. Some of his paintings can be seen in the American Gallery, Greatest American Painters: http://americangallery.wordpress.com/2011/01/31/herman-n-hyneman-1849-1907/

Son Samuel Morais Hyneman was a lawyer of some renown, having been admitted to the Philadelphia Bar in 1877. In the 1880s and 1890s, he was a director of the Hebrew Education Society. A few years later, in 1893, the large Hyman Gratz trust came into the control of Mikveh Israel with the expressed purpose of establishing and maintaining a Jewish College in Philadelphia. Samuel Hyneman served on the Permanent Committee to establish Gratz College and make Gratz’ dream a reality. He also helped establish the Association of Jewish Immigrants. Samuel Hyneman also served on the Board of Managers of Mikveh Israel, elected in 1894 as one of the Adjunta (Directors).

Son Samuel Morais Hyneman was a lawyer of some renown, having been admitted to the Philadelphia Bar in 1877. In the 1880s and 1890s, he was a director of the Hebrew Education Society. A few years later, in 1893, the large Hyman Gratz trust came into the control of Mikveh Israel with the expressed purpose of establishing and maintaining a Jewish College in Philadelphia. Samuel Hyneman served on the Permanent Committee to establish Gratz College and make Gratz’ dream a reality. He also helped establish the Association of Jewish Immigrants. Samuel Hyneman also served on the Board of Managers of Mikveh Israel, elected in 1894 as one of the Adjunta (Directors).

Son Jacob Ezekiel Hyneman was born in Richmond, Virginia on August 5, 1843, but moved with his family to Philadelphia in 1850. Jacob Hyneman became a military man. He received his college education at Strasburg Academy in Lancaster County, PA and enlisted in the army to fight for the Union in August 1862. He fought and was wounded in numerous battles of the Civil War, including Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and Appomattox Court House. He was present at Lee’s Surrender on April 9, 1865. After the war, he joined the National Guard of Pennsylvania, where he rose to First Lieutenant in 1880, and Quartermaster with the rank of Captain in 1883. He resigned from the National Guard in 1891 and started an Insurance Agency, which grew to be one of the largest in Pennsylvania. He devoted much time and money to furthering many of the principal Jewish agencies in Philadelphia. Jacob and Samuel both were long-time members of the Union League of Philadelphia. He also served with Samuel on the Board of Managers of Mikveh Israel.

In Samuel Hazards United States Commercial and Statistical Register of 1840, published in Philadelphia, he notes a Meeting of the Israelites in Richmond, August 18, 1840, in which four resolutions were adopted. These were described in detail. The first was that “the Israelites of the State of Virginia unite in sentiments of sorrow and sympathy, for the unparalleled cruelties and sufferings inflicted on their innocent and unoffending brethren of Rhodes and Damascus”. Another expressed gratitude toward their Christian brethren for helping to prevent future aggressions. The third resolved that the Israelites of Virginia would unite with their brethren throughout the Union in diffusing the blessings of civil and religious liberty. The last resolved to appoint a committee that would meet and confer with other Israelite groups in order to carry out resolutions. Isaac Hyneman was appointed to this committee, and his partner and brother-in-law Jacob Ezekiel was appointed Secretary.

Bibliography

- www.geni.com

- Robert P. Swierenga, The Forerunners, Dutch Jewry in the North American Diaspora, 1994

- Henry Samuel Morais, The Jews of Philadelphia, 1894

- Fifty Years’ Work of the Hebrew Education Society of Philadelphia 1848-1898

- Samuel Hazard, Hazard’s United States Commercial and Statistical Register, Volume 3, Philadelphia, 1841

- Wikipedia