Abraham Sulzberger and the Jewish Hospital

This week we remember the Hashcabah of our dear friend and lifetime member of Mikveh Israel, Berthold Levy who passed away a couple of years ago at the age of 97. Levy was the great grandson of Abraham Sulzberger, who was the first of Bert’s ancestors to come to Philadelphia and begin a long legacy of outstanding and influential members of Mikveh Israel, the wider Jewish community in Philadelphia, and the broader secular society in Philadelphia in general.

Abraham Sulzberger was born in Heidelsheim in Baden, Germany on May 20, 1810. His father, Solomon (Meshullam) Sulzberger, had been a Rabbi there and Abraham followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming a scholar in Jewish texts as well as serving as Hazan, reader, shohet (slaughterer) and teacher in his local congregation. He married Sophia Einstein and had six children, including the famous Judge Mayer Sulzberger who was born on June 22, 1843, and was destined to be the most prominent and influential Philadelphia Jew of his generation, and in 1894 was the first Jew to sit as a judge of the Court of Common Pleas.

During the uprising of 1848 in Germany there were reprisals against the Jews, and Sulzberger decided to relocate his family to America. His older brother Leopold had already settled in Philadelphia in 1838, so Abraham prepared the family for the long journey to join him there. The journey began with a trek that lasted for months across Germany and France in a wagon, eventually reaching the French port city of Le Havre. There they boarded a transatlantic steamer called the Splendid, and arrived in New York Harbor on August 11, 1849. From there they made their way to Philadelphia and established themselves in the city and joined Mikveh Israel. The following year, Sulzberger was one of 8 charter members who founded the Har Sinai Lodge of District No. 3 of the B’nai B’rith. Sulzberger served as its president for the next 25 years.

During the Civil War, Rev. Isaac Leeser, the former Minister of Mikveh Israel, was very concerned about the wounded Jewish soldiers in the army hospitals. He obtained a hospital pass from his friend General Charles Collis, who was married to Septima Levy, formerly of Charleston. Sulzberger would accompany Leeser on hospital visits to the Jewish wounded. It was just after the Battle of Gettysburg in early July of 1863 that Sulzberger and Leeser began discussing a plan for a hospital. By this time, Leeser had already separated from Mikveh Israel on somewhat unfriendly terms and had become the minister of a new congregation Beth El-Emeth. Because Leeser was a major force behind this initiative, Mikveh Israel was reluctant to work directly with him on the project.

They turned next to the new Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel, confident that they find support for the project given the many denominational Christian hospitals that had been built over the previous generation by the Catholic (St. Josephs) and Episcopal Churches, and by the German Christian population (Lankenau). Keneseth Israel was founded in 1847 as an Orthodox synagogue, and in the years just before the first synagogue building was dedicated in 1854, Abraham Sulzberger had helped the congregation as one of the hazanim (readers). Both Rev. Isaac Leeser and Rev. Sabato Morais had taken part in the dedication ceremony of the new building. Within a few years however, the congregation, under the leadership of Rev. L. Naumburg, adopted some of the “innovations” of the Reform Movement such as a mixed choir and the introduction of an organ into the service. Under the leadership of Rev. Dr. Solomon Deutch, who became the Rabbi in 1857, and Rev. Dr. David Einhorn who took over in 1861, the congregation fully became a Reform Congregation. As such, the congregation objected to the strict observance of Kashrut insisted by Sulzberger and Leeser for the new hospital and refused to help.

Out of options with the religious institutions, they turned to the B’nai B’rith. Sulzberger was the past President of the local lodge, and Leeser, after initially resisting and opposing the order during its early years as secret society, had joined and moved up through the ranks to a top influential position as Vice-President of the Elim Lodge. During the annual meeting of the Grand Lodge No. 3 of the B’nai B’rith on August 14, 1864, Sulzberger, in calling attention to the fact that three Jews within the previous six months had died in various area Christian hospitals without the option of being fed kosher food or being administered Jewish rites, offered resolutions asking for the appointment of a committee to consider the subject of organizing a Jewish Hospital. He further noted that both New York City, Cincinnati, and the larger cities in Europe had seen the need and built hospitals for their Jewish populations. It was a discredit, they argued, to the Jewish population of Philadelphia to allow their brethren to be cared for and possibly die in the care of strangers who did not understand or approve of the obligations of Jewish law.

That committee was established and included Sulzberger, Rev. Isaac Leeser, Samuel Weil and others. Within a few days a circular was sent to every B’nai B’rith Lodge and all of the congregations and Jewish societies in the area requesting appointments for committees. On December 4, the first meeting of this joint convention was held during which a plan was prepared, and a constitution and by-laws were framed and presented. On Sunday February 19th, 1865, these were ratified by a large meeting of the area Jews at a meeting held at the National Guard’s Hall on Race Street below Sixth. Officers and managers were appointed, including President Alfred T. Jones, Vice President Isadore Binswanger, Treasurer Samuel Weil, and Secretary Mayer Sulzberger. Abraham Sulzberger’s home at 977 North Marshall Street became the temporary headquarters of the provisional committee for the hospital.

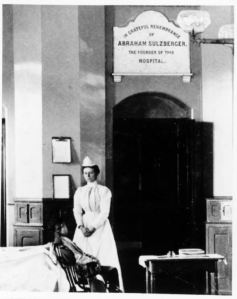

The Association was incorporated on September 23, 1865 and a lot was soon purchased at 56th Street and Haverford Road in West Philadelphia for $19,625. The Jewish Hospital opened the on August 6, 1866 along with a home for the aged. It started with 22 beds and linens donated by philanthropist Moses Rosenbach. During the first year 71 patients were treated and 5 people were admitted to the old-age home. In 1873, the hospital moved to greatly expanded facilities at Old York Road and Olney Avenue. In 1952, after merging with Northern Liberties Hospital and Mount Sinai Hospital to form a single medical center, it evolved into the Albert Einstein Medical Center. It was very appropriate that Einstein granted permission to use his name for the non-profit organization, as Abraham Sulzberger’s wife Sophia was an ancestor of Albert Einstein.

- www.geni.com

- www.ancestry.com

- Wolf, Edwin, II, and Maxwell Whiteman. The History of the Jews of Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the Age of Jackson. 1957

- Lance J. Sussman, Isaac Leeser and the Making of American Judaism, 1995

- Maxwell Whiteman, Mankind and Medicine: The making of Albert Einstein Medical Center, 1966

- Robert P. Swierenga, The Forerunners: Dutch Jewry in the North American Diaspora, 1994

- Henry Samuel Morais, The Jews of Philadelphia, 1894

- Arthur Kiron, The Mayer Sulzberger Collection, Biography, Library of the Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, 1994

- Hasia R. Diner, A New Promised Land: A History of Jews in America, 2000

- Fifty Years’ Work of the Hebrew Education Society of Philadelphia 1848-1898

- Samuel Hazard, Hazard’s United States Commercial and Statistical Register, Volume 3, Philadelphia, 1841

- Wikipedia

The Synagogue Buildings

THE FIRST BUILDING Third and Cherry Streets

THE FIRST BUILDING Third and Cherry Streets

Communal Jewish life in Philadelphia started in the early 1740’s. The small but growing congregation first worshipped together in a small rented house on Sterling Alley, which ran from Cherry to Race Streets, between 3rd and 4th Streets. In 1761, the congregation borrowed a Torah scroll from Shearith Israel in time for the High Holidays of that year. An attempt was made that year to build a synagogue building, but the plans were abandoned at that time due to lack of funds. Over the next ten years, several more Jewish families settled in the city, and in 1771 the tiny congregation incorporated as Kahal Kadosh Mikve Israel and named a president, officers, and a board of trustees. They acquired another Torah scroll and some prayer books from London, and received a gift from Shearith Israel of a silver reading pointer (yad).

On February 22, 1773, at a meeting of the Mahamad (Board), it was resolved that they would collect money in order to fund a synagogue building. The subscription was to last for 3 years. The outbreak of the revolutionary war in 1776 put a temporary halt to their plans. As Jewish refugees from other colonial cities streamed into Philadelphia, they soon outgrew their tiny space and moved to the second floor of a rented house on Cherry Alley between 3rd and 4th Streets, about 2 blocks from the present building. In 1782, with a substantial contribution by Haym Salomon and spiritual guidance from Rev. Gershom Mendes Seixas, the congregation purchased land and erected a building on the north side of Cherry Street, west of 3rd.

The building was dedicated on September 13, 1782 in an elaborate ceremony under the direction of Jonas Phillips, Parnas, and Rev. Seixas. Haym Salomon was given the honor of opening the doors to the new synagogue building. The following was quoted from the address which was presented to the Governor and Executive Council of Pennsylvania:

“The Congregation of Mikve Israel (Israelites) in this city, having erected a place of public worship which they intend to consecrate to the service of Almighty God, tomorrow afternoon, and as they have ever professed themselves liege subjects to the Sovereignty of the United States of America, and have always acted agreeable thereto, they humbly crave the Protection and Countenance of the Chief Magistrates in this State, to give sanction to their design, and will deem themselves highly Honored by their presence in the Synagogue, whenever they judge proper to favor them.”

THE SECOND BUILDING Third and Cherry Streets

THE SECOND BUILDING Third and Cherry Streets

As the congregation grew in the first quarter of the 19th century, more space was needed for the congregation. The great architect William Strickland was engaged to design a new building. Though the cornerstone was laid on September 26, 1822, the building was finally completed and dedicated in a beautiful ceremony on January 21, 1825. The design was inspired by the Neo-Egyptian Style of architecture which had become popular in England after the British General Nelson’s victory at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, and in France after Napoleon’s victory in the Battle of the Pyramids. The new Mikveh Israel synagogue building was the first example of this style in Philadelphia. It was a two-storied building with a slate roof with skylight and was twice the size of the original building it replaced. The seats were arranged in two semi-circular blocks on either side of the ark, which was in the eastern end of the building. The dedication ceremony was performed by newly arrived Rev. Abraham Israel Keys, assisted by Rev. Moses Peixotto of Shearith Israel.

THE THIRD BUILDING Seventh and Arch Streets

THE THIRD BUILDING Seventh and Arch Streets

This building remained for some 30 years before the congregation, swelled by waves of immigrants in the 1840s and 1850s, required larger quarters. Several sites were considered for the new synagogue building, and finally a property was purchased at 117 N. 7th Street in 1858 for $15,100. The cornerstone was laid on May 9, 1859. This third building was designed by John McArthur, who later designed Philadelphia’s City Hall, the tallest and largest building in America at the time. An elaborate dedication ceremony was held on May 24, 1860, with Rev. Dr. Sabato Morais officiating. Instrumental music was furnished by an orchestra, and the vocal selections were arranged by Dr. Morais, based on melodies from the Spanish and Portuguese Congregation of Livorno, Italy. Though the McArthur building lacked the charm of the Strickland synagogue, and did not display any of the more elaborate style of the City Hall building he designed a decade later, it was still a handsome structure of brick and stone with an attractive interior. The sanctuary was situated on the second floor, with galleries above. The first floor was used for school meetings, lectures, committee meetings, and administrative offices. In the rear of the building, was a small house used for the Sexton’s quarters.

THE FOURTH BUILDING Broad and York Streets

THE FOURTH BUILDING Broad and York Streets

In 1893, the congregation was notified that a trust, created by Hyman Gratz, became vested in the congregation “in trust for the establishment and support of a college for the education of Jews residing in the city and county of Philadelphia”. Hyman Gratz was the son of Michael Gratz and Miriam Simon Gratz, who were original founding members of Mikveh Israel; Michael was a past Parnas of the congregation. Hyman had been treasurer of Mikveh Israel for 33 years and hand made his money in the insurance business. He created an annuity in the 1850s with a substantial sum of money, which he left in trust in 1856. The proceeds of the trust were to be paid to Mr. Gratz until his death, and then to is adopted son Robert. Only if Robert Gratz died without “lawful issue” (children), would the annuity be paid to Horace Moses, a nephew of Hyman Gratz. Then, only in the case that Horace Moses would die without lawful issue, would the entire trust estate be passed to Mikveh Israel for the establishment of the college.

Hyman Gratz died just six weeks after establishing the trust at the age of 81. Neither his adopted son Robert, nor his nephew Horace Moses had any children. Robert died in 1877, and Horace died in 1893. Just a few weeks after his passing, the Parnas of Mikveh Israel, Horace Nathans, appointed a committee to explore ways to fulfill the terms of the trust. That committee, which was afterward reconstituted as the first board of trustees, ultimately recommended establishing Gratz College, which was founded just two years later in 1895.

Gratz College officially opened its doors in the 1897-1898 academic year with 29 students and a faculty of three. The original classes of Gratz College were held in the Mikveh Israel synagogue. Over the next 10 years, the college grew and needed its own space for classes and administration. In 1907, Dropsie College was founded, funded from a trust bequeathed by its benefactor Moses Dropsie, and established by the leaders of Mikveh Israel as the Dropsie College of Hebrew and Cognate Learning. In 1909, Mikveh Israel established the Mikveh Israel School of Observation and Practice, the first Jewish elementary school of its type in America.

Plans were created to build a campus to house all three institutions, as well as a synagogue building for Mikveh Israel, as the directors and administrators of the educational institutions were also the leaders of the congregation. The synagogue building was funded by a donation bequeathed to the congregation of $100,000 by Samuel Elkin in the name of his parents Abraham and Eve Elkin, early members of the congregation. Mr. Elkin died on March 12, 1907, and the executor of his will, his nephew Henry G. Freeman, Jr., stipulated that $40,500 be used to purchase the site, and that the remaining $59,500 be used to construct the building. This was acceptable to the congregation and a committee was appointed to create plans for the new building at Broad and York Streets, as well as the other two buildings to house Gratz College and Dropsie College. They selected the architect firm of Pilcher and Tachau of New York.

Tachau had designed many synagogues in his portfolio. The synagogue building was designed as an imposing one-story, fire-proof, limestone building in the Neo-Roman style. Mikveh Israel anchored the site, erected on the corner, with Gratz College behind the synagogue, and Dropsie parallel along Broad Street, set back behind a small lawn. The entrance foyer was elegant and served as a social gathering space for before and after services. Galleries for the women were accessed by broad, low stairways, and comprised a wooden seating section just behind and slightly above the men’s sections which were positioned opposite each other in the identical configuration of the present building. The building held 300 seats in the men’s section and 200 seats in the women’s section.

The dedication ceremony was very elaborate. It featured seven circuits around the tebah, in between which were recited different prayers, including memorial prayers for the benefactors and the former ministers, prayers for the congregation and the government, several psalms, and a ceremonial lighting of the perpetual lamp by former Parnas Charles J. Cohen, Esq. Following the circuits were addresses given by Rev. Henry Pereira Mendes, minister of Shearith Israel, Rev. Leon H. Elmaleh, minister of Mikveh Israel, and finally a prayer by the Chief Rabbi of the Central Talmud Torah school, Rabbi B. L. Levinthal. The chanting was led by the Shearith Israel choir, under the leadership of Mr. Leon M. Kramer as a contribution by the officers of Congregation Shearith Israel for the occasion.

THE FIFTH BUILDING Independence Mall

THE FIFTH BUILDING Independence Mall

The congregation had moved to Broad and York to follow the Jewish migration to that part of the city. From the beginning of the 20th century, North Broad Street was home to some of the wealthiest people in Philadelphia who had built mansions along the wide boulevard. Fashionable shops, restaurants, and other businesses lined the corridor. The Jews established a thriving community in this neighborhood. But by the end of World War II, the upwardly mobile children of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, whose parents had been factory workers and laborers in the city’s working-class neighborhoods, began to leave the city and move further north into the near suburbs. The well-established Broad Street synagogues Keneseth Israel, and Adath Jeshurun had moved into the suburbs in the 1950s.

It was around this time that the congregation started contemplating following suit and leaving the quickly declining neighborhood. In 1952 they appointed a committee to study the possibility of relocating the congregation, and in the spring of 1953, it presented its report to the board. The conclusion was that the only way to survive would be to move. The committee wrote, “To Continue as at present is to continue a process of attrition. The location is in a non-Jewish, decaying neighborhood. It no longer ‘serves its original purpose’ “. Two proposals were placed before the congregation. One was to move to the northern edge of the city thus serving the many congregants that had moved to the near northern suburbs. The other was to move the congregation to the historic district of Philadelphia, taking advantage of its rich history as a colonial synagogue which had not only shaped Jewish life in the city, but had contributed to the formation, viability, and character of the nation itself. The committee envisioned a synagogue that would serve its members’ religious needs, but also serve as a living symbol to society at large. In 1953, they hired Architect Louis Magaziner to draw up plans for a new synagogue on Independence Mall.

The congregation was deeply divided for many years between the two possible moves which were in opposite directions both literally and ideologically. By 1960 however, the board and the congregation were convinced that a move to the historic district would be the best choice, and at the annual congregational meeting in November, the members unanimously approved the purchase of a lot in the Independence Mall area and the subsequent removal of the synagogue to that location. It took most of the next 10 years to negotiate for the land, but eventually a lot was acquired for less than $200,000 from the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority.

In 1961, the congregation hired the prominent architect Louis Kahn. The decision was designed to inspire investors and encourage membership. Kahn’s designs received wide recognition and acclaim both within the city and in New York. Unfortunately, the projected cost of the Kahn project was estimated at five Million dollars, which the congregation determined to be far out of its reach. They were also frustrated with the working relationship with the architect himself. There was also some urgency as 1970 approached. If the synagogue was to participate in the bicentennial festivities, when people from all over the country would be pouring into Philadelphia to celebrate the symbols of its history, the building needed to be completed as quickly as possible. They realized that surrounding the Liberty Bell, which was at the center of the mall, would stand the icons of the nation’s founding and that Mikveh Israel should take its rightful place among them.

Under the leadership of Ruth Sarner, the building committee dismissed Mr. Kahn and redrafted a scaled down project with the architect firm of Harbeson, Hough, Livingston, and Larsen. The new project was estimated over three million dollars, but by 1974 only $400,000 had been raised. In a move designed to appeal to investors, the newly incorporated Museum of American Jewish History was placed at the forefront of the project. The design was further scaled back and after selling the museum the entire lot for $1 in exchange for the right to occupy part of the building in perpetuity, the museum received grants from the Bicentennial Commission and the city of more than $200,000, and borrowed another $900,000 to complete the project.

On September 12, 1976, in an elaborate ceremony presided by Rabbi Ezekiel N. Musleah, the doors to the new synagogue building were opened and the synagogue was dedicated. The ceremony began with a procession from the Liberty Bell Pavilion to the synagogue with all of the Torah scrolls. Following were seven circuits around the tabah, in between which were prayers for the congregation and for the government, a bicentennial prayer, and a prayer for peace. Afterwards, addresses were given by Haham Solomon Gaon, Rabbi of the Spanish & Portuguese Bevis Marks synagogue of London and professor of Sephardic Studies at Yeshiva University, and Rabbi Gerson D. Cohen, Jewish historian and the chancellor of the Jewish Publication Society. Rev. Dr. Louis G. Gerstein, minister of sister congregation Shearith Israel in New York and Rabbi M. Mitchell Serels of the Yeshiva University Sephardic Studies Program also joined in the ceremonies.

A hand-written letter from President Gerald Ford was presented by David Lissy, associate director of the President’s Domestic Council. Lissy himself performed his Bar Mitzvah ceremony in the previous synagogue building on Broad Street. His father, the late Frank M. Lissy, was the Corresponding Secretary of the congregation. Ford wrote:

“In the year of our bicentennial, the dedication of your new synagogue carries special meaning. It marks the continuity of life and tradition of your congregation. It also reflects the vision of George Washington and our other founding fathers that in a free land each should be free to worship as he chooses.”

Bibliography

• Americanjewisharchives.org

• John Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, History of Philadelphia, 1609-1884, Volume 2, 1884

• Wolf, Edwin, II, and Maxwell Whiteman. The History of the Jews of Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the Age of Jackson. 1957

• Susan G. Solomon, Louis I. Kahn’s Jewish Architecture: Mikveh Israel and the Midcentury American Synagogue, 2009

• Dedication of the New Synagogue of Congregation Mikve Israel at Broad and York Streets on September 14 1909 Elul 29 5669, ASW Rosenbach

• Jerry Kutnick, Serving the Jewish Community, Pursuing Higher Jewish Learning, Gratz College in Historical Perspective, 1998

• http://www.urbanoasis.org, Temple University and North Philadelphia, 125 Years of Linked History

• http://www.americanbuildings.org, Mikveh Israel Center, proposed building for Independence Mall, Philadelphia, PA

• Jordan Stanger-Ross, Neither Fight Nor Flight, Urban Synagogues in Postwar Philadelphia, Journal of Urban History, 2006

• American Jewish Historical Society Quarterly, Volume 11. Cyrus Adler, President, 1903

• Henry Samuel Morais, The Jews of Philadelphia, 1894

• “Ford Extols Philadelphia Synagogue”, Jewish Telegraphic Agency, 1976

• Arthur Kiron, The Professionalization of Wisdom: The Legacy of Dropsie College and Its Library

• The American Sephardi, Volume 9, Yeshiva University Sephardic Studies Program, 1978